From the desire to clean up a dirty old town to a former editor’s campaign to clean up some dirty old men, Chris Lloyd airs some dirty washing and irons out a misunderstanding.

IN the pale moonlight on a long exposure, ethereal steam drifts gently from the mouths of the cooling towers.

The water vapour looks as pure and as soft as summer cloud – but for decades the people living beneath complained of the “artificial drizzle” that rained down on them.

The towers dominated Darlington’s skyline for 40 years, and although Douglas Jefferson, The Northern Echo’s famous first chief photographer, turned them into objects of beauty one still night, to the townspeople in the tight terraces, they were anything but.

Their discharge mingled with the soot and smuts tossed out of the chimneys of the steam trains on the East Coast Main Line, and together they created a very dirty drizzle that made it impossible to dry anything white on a washing line.

Darlington’s first power station was built where Duncan Bannatyne’s gym is today, in Haughton Road. It was located beside the main line so it could easily be fed coal.

It commenced generation in December 1900, but needed replacing in the Thirties. Teesside’s industries were requiring more and more power and so, at first, the National Grid considered building a megastation nearer Middlesbrough.

But, as international tension grew, it was decided that a series of smaller stations was strategically safer, and Darlington got the go-ahead to rebuild.

“When we moved into Middleton Street in 1939, when I was five, they were replacing the old wooden cooling towers,” says Eileen Tunstall.

“A friend of my brother’s was killed while working on the construction – a girder fell on his head. He was only young. There were quite a lot of accidents.”

The £324,000 power station was ready by May 1940 when it came to the attention of the notorious turncoat Lord Haw-Haw. In one of his propaganda broadcasts he warned Darlington that it was now of strategic importance and would be bombed.

“One night there was a dogfight between a German plane and one of ours,”

remembers Eileen.

“It was British Summer Time and still light. There were no sirens going off, otherwise we would have been in the air raid shelter, and all the neighbours in the street were watching it.

“I was worried in case one of the planes crashed down into the cooling tower nearest us.”

This was probably August 15, 1940 – a date that will feature in a future Echo Memories.

The three towers – plus three towering cricket stump chimneys – generated power until October 19, 1976. They were demolished on January 28, 1979, and the chimneys came down in 1982.

THE lights on the left of Douglas Jefferson’s photograph of Brunswick Street belong to the Golden Lion pub.

The first Golden Lyon appears to have arrived in Darlington in the early 1770s when Adam Bell – “late waiter at the Golden Lyon in Durham” – set up in business.

The Golden Lion in Brunswick Street was built in the 1850s or 1860s as Darlington sprawled over the Skerne. It looks to have been an unprepossessing neighbourhood boozer, but in 1882 a Mrs Martland, a widow, bought it for £1,000 from her brother, John Edmondson.

When she died childless and intestate a few years later, her brother’s widow, Mary Jane, claimed the property as her own – even though she still had the £1,000 proceeds from the sale.

The case trailed through the courts for the best part of two decades before the Martland family won the right to keep the pub.

By 1905, it was valued at £1,525. It had a smoke room and a tap room, plus out the back were two club rooms over the spirit store and the three-stalled stable.

The Lion closed in May 1961 and was cleared along with the surrounding slums soon after.

WT STEAD: an apology.

From the chief executive of Darlington Partnership to the ladies of North Cowton Women’s Institute, there was a mis-reading of last week’s column that does not reflect well on the writer.

Stead is the most famous editor of The Northern Echo.

He was probably the most famous person on board the Titanic when it struck an iceberg in 1912.

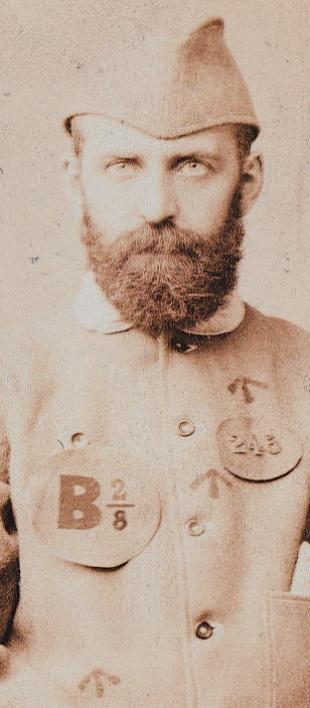

Last week, we showed a rare carte de visite depicting Stead in his prison uniform, which is soon to be auctioned by Tennants of Leyburn.

In 1885, Stead was determined to expose the trade in young girls who, in their thousands, were sold into slavery in London’s brothels. He spent weeks trawling the capital’s seedy streets for evidence.

“I am living in hell,” he wrote. “Oh, it is awful this abode of the damned. I go to brothels every day and drink and swear and talk like a fiend from a bottomless pit.”

Beyond evidence, he needed incontrovertible proof.

So, through an intermediary, he bought a 13- year-old girl from her drunken, dissolute mother.

He paid £3 cash, and then sent a further £2 when a doctor examined the girl and declared her to be virgo intacta.

The girl was then taken to a brothel off Regent Street where she was undressed and put into bed.

A chloroform-impregnated handkerchief was placed over her face to make her woosy and to dull the pain of what her first customer was about to do to her.

That first customer was Stead himself.

In a lurid article, using sensational and titillating headlines such as “The Violation of Virgins” and “Strapping Girls Down”, he explained what happened next.

“The door opened, and the purchaser entered the bedroom. He closed and locked the door. There was a brief silence. And then there rose a wild and piteous cry – not a loud shriek, but a helpless startled scream like the bleat of a frightened lamb. And the child’s voice was heard crying, in accents of terror: ‘There’s a man in the room! Take me home; oh, take me home!’ *************** And then all once more was still.”

Through his use of asterisks, Stead clearly wanted to at least hint to his readers that that he had had sex with the girl, and 125 years later some readers of this column came to the conclusion that that is what happened.

In truth, Stead had stepped into the room causing the drugged girl – Eliza Armstrong – to scream out.

Then he had stepped outside, the scream apparently confirming to other brothel users that the deed had been done.

Immediately afterwards, Stead had Eliza whisked off to a Salvation Army safe house in Paris while he serialised the sordid story over five days in his paper, the Pall Mall Gazette.

It sold enormously. By day four, he’d run out of ink, so his old friends in the printing trade in County Durham – he’d edited the Echo between 1871 and 1880 – rushed some down to him.

By day five, WH Smith refused to stock the paper.

Eager readers besieged the Gazette offices, rioting to get their hands on the latest copy. Indignation meetings were held all over London – at the biggest, in Hyde Park, up to 250,000 turned out to register their disgust at the trade.

The Criminal Law Amendment Act was rushed through Parliament, raising the age of consent for girls from 13 to 16 and outlawing “any act of gross indecency with another male person”.

This was to protect young boys, who were also cruelly abused in brothels, but effectively banned homosexuality – Oscar Wilde was famously imprisoned by Stead’s Act.

But Stead had many enemies, from MPs who profited from the sex trade – one MP offered to sell him 100 maids at £25 each – to lords who indulged their fantasies in it.

Some felt Stead had outrageously broken all the taboos by discussing sex in public, and others felt he had brought immense shame on the country by airing its dirty linen for all the world to see.

Plus Mrs Armstrong, having drunk her £5 away, realised she was not coming out of the scandal well. Her husband, Charles, thrashed her and then went with the police to Paris to try to find Eliza.

He wasn’t much use as he twice succumbed to the lure of the Parisian ladies of the night and was then arrested by gendarmes for being drunk and disorderly.

The authorities scrabbled around for reasons to prosecute Stead. They realised he hadn’t obtained Eliza’s father’s permission and so charged him with “felonious abduction of a girl under 14”.

Judge Henry Charles Lopes ruled that it didn’t matter how high-minded and moral Stead’s motives might be, if he had taken the girl without her father’s permission, he was guilty.

(It was said that the judge’s views were coloured by the fate the previous year of his close colleague, Judge Sir Charles James Watkin Williams, 54. His Honour’s reputation had been posthumously dishonoured because he had collapsed and died only 15 minutes after entering a brothel accompanied by a nubile young lady called Miss Nellie Banks.) Stead had. He was guilty.

Judge Lopes sent him to Holloway.

Yet he was proud of what he had done. He had introduced Britain’s first child protection Act, which was copied around the world.

No longer were poor children regarded as the worthless sexual playthings of the immoral rich.

To celebrate his achievements, every November 10 afterwards, Stead wore his prison uniform in the streets and in his office – looking much like the carte de visite that comes under the hammer on March 3.

■ Greatly assisted by Maiden Tribute: A Life of WT Stead by Grace Eckley (available at amazon.co.uk)

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here