“WE bought it for this room,” says John Hawgood. “Ten years ago, when Mary was mayor, we were looking at the flat next door, and looked in though the window and saw this, and had to have it. Fortunately, it came up for sale soon afterwards.”

He’s standing in one of the finest rooms in the city of Durham. It’s big enough for a banquet, with its walls and ceiling artistically covered with decorative plaster, and, through the large French windows, there’s a glorious view of the cathedral through the winter trees.

It is one of five apartments in St Anne’s Court, the Georgian townhouse in Framwellgate that appeared in Memories last week. Lots of people responded to our appeal by offering information about it; Mary and John responded by offering an invitation to look round it.

It is a staggering room, about 50ft by 25ft, with apples, pears and peaches hanging from the ceiling, roses and flowers climbing the walls, and leaves and vines creeping around the monumental shapes and shields.

It was built in the middle of the 18th Century – judging by the vaulted brick rooms beneath the dining room, there was an earlier, substantial building on the site.

No one knows the identity of the grand personage who first lived in it, if indeed it was a domestic building. No one knows its original name.

And no one knows for sure who did the plasterwork – or stucco – although its intricacy and styling suggests it was Giuseppe Cortese, an Italian stuccoist who worked in the North-East from the 1720s to the 1760s. He was at the height of his powers in the 1750s when he worked at nearby Croxdale Hall, Elemore Hall, Aykley Heads House and Coxhoe Hall. His work can also be seen on the Temple of Minerva in Hardwick Park, near Sedgefield, and at Studley Royal near Ripon, plus at Fairfax House and the Treasurer’s House in York. If you were rich 250 years ago and wanted rococo stucco, Cortese was the man to get you plastered.

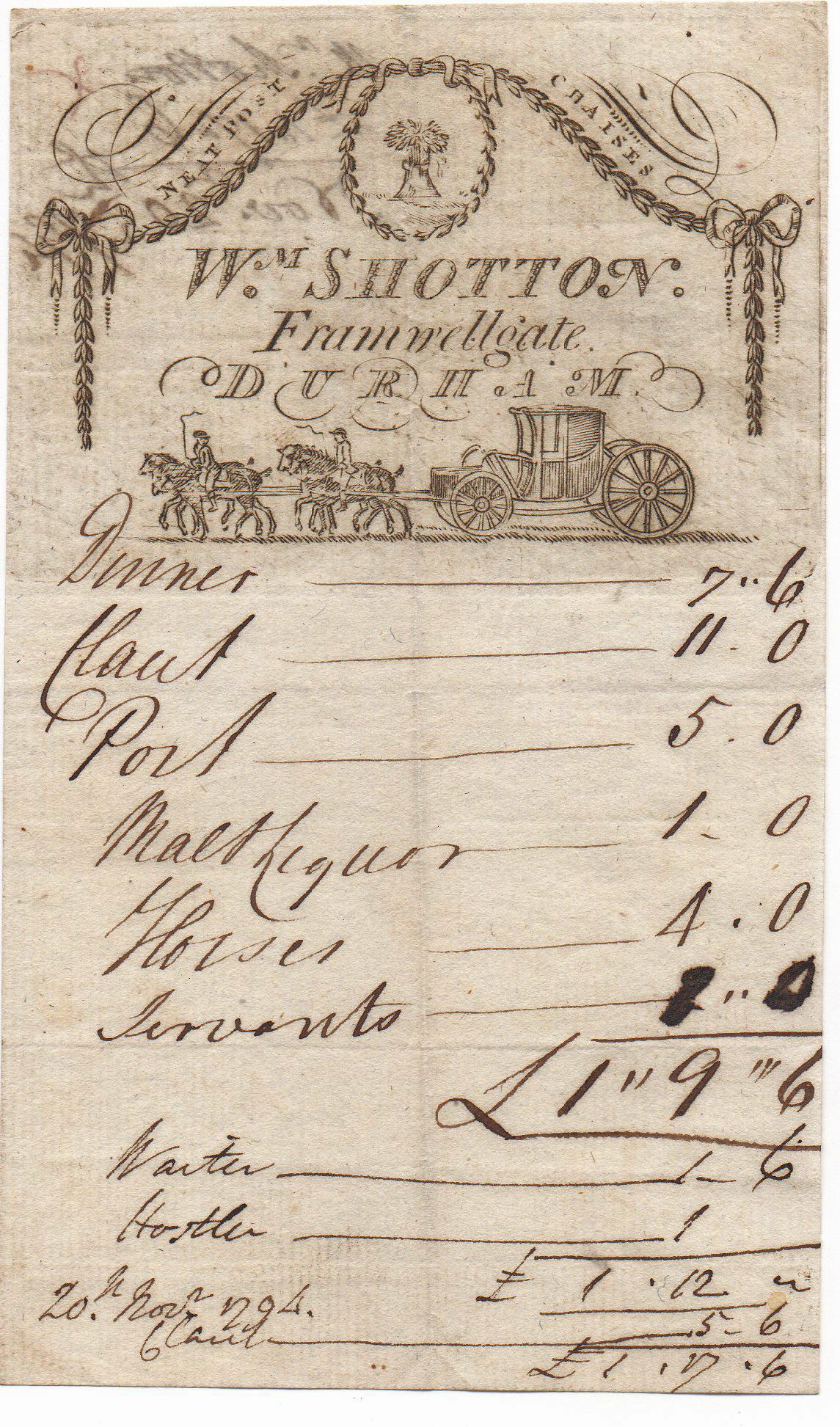

By the end of the 18th Century, the building was an inn called The Wheatsheaf. The large room, with its splendid views, was probably the fine dining room, although the tables and chairs could have been cleared away so it became a useful assembly or concert room – it is probably too small for a full-blown ball.

In the 1850s, The Wheatsheaf was bought by the Catholic church. Irish labourers were being attracted into the Durham coalfield. Many of them were living in the slums of Framwellgate and Milburngate, and a new church was needed. The Wheatsheaf was used for worship until the Church of Our Lady of Mercy and St Godric was completed in 1864 on the higher ground above it – it is said that there is a lost tunnel leading from the altar of the church down to The Wheatsheaf.

The inn then became the presbytery for the church, and a part of it was the home of the nuns – a convent – who taught in St Godric’s school which was built on top of the inn’s former stables.

By good fortune, the building was just elevated enough to avoid the riverside slum clearances of the 1930s, and the A690 road-building scheme of the 1960s. But once the school moved out to Newton Hall and the nuns departed, it faced an uncertain future – which is why our 1959 photograph shows it looking down-at-heel and distinctly worried.

In the 1970s, it found a use as the Castle Chare Arts Centre. “One of our sons played his first gig in here with his band, and our daughter came here for a computer course,” says Mary. “It is amazing that all of this plaster survived when you think of people like my son messing round in here with their guitars.”

Amazing indeed. Martin Roberts, formerly English Heritage’s Inspector of Historic Buildings in the North-East, says: “The great glory of the building is the rococo room which is probably the biggest and equal best (with Aykley Heads House) mid 18th Century plasterwork in the city – nothing on the peninsula comes near it!

“Towards the end of its life as an arts centre, a lot of very well-meaning lads redecorated it without getting Listed Building Consent – it is Grade II* of outstanding national importance because of the room. They turned the subtle, nicotine-stained decor into something more like a fairground organ, totally destroying the look of the room.”

The flowers, fruits and leaves were painted individual garish colours. A long battle ensued between the conservationists and the decorators, who eventually lost their appeal and were ordered to repaint the room in a muted soft cream.

Martin says: “This prompted the Durham Advertiser to come up with the excellent headline: ‘Fresco fiasco comes unstuccoed’.”

About 15 years ago, the building was converted into apartments along with the former school next door, and so Mary and John, who spent a previous portion of their lives rescuing Crook Hall near Durham City, live amid the splendour of the 18th Century rococo stucco.

“I think we paid more than for the apartment than they were asking for it, just to make sure we got it,” says Mary, proudly. “We feel it was worth it.”

It certainly was.

We are very grateful to Mary and John Hawgood for their invitation, to Martin Roberts for his information, and to Peter Jefferies and Michael Richardson of the Gilesgate Archive for their pictures. Many thanks to everyone else who got in touch

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here