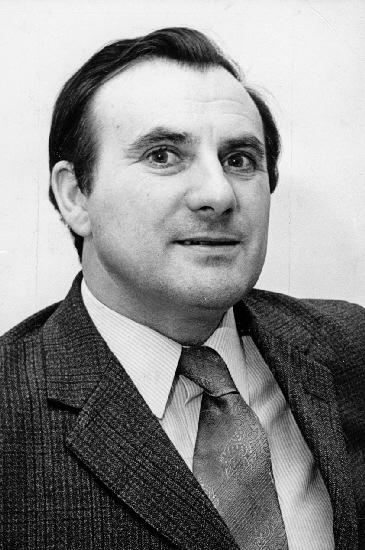

The column pays tribute to Arnold Hadwin – friend, mentor and a man who always got the job done, no matter what.

ARNOLD Hadwin, the man who took the great risk, has died suddenly, aged 82. He was editor, Commando, community crusader and friend, a man of vigorous action and uncompromising principle who – for now it may be told – cheated his grandbairns at cards.

He left school at 16, became a reporter on 15 shillings a week in the Northern Echo’s Bishop Auckland office, was told that the modest remuneration was because for the first few weeks he’d simply be a nuisance.

“I vowed,” said Arnold, “to be a nuisance for the rest of my life.”

He joined 40 Commando despite being an inch too short, won an Oxford scholarship and gained a degree in politics, philosophy and economics, edited – among other titles – the Northern Despatch in Darlington, became president of the Guild of British Newspaper Editors, was made OBE in 1982 and inspired, invigorated and empowered very many.

Sara, one of his two daughters who themselves became senior media professionals, had interviewed her father in 1976 for an O-level English project. “Throughout my working life,” he told her, “I’ve never ceased to wonder at my good fortune in being paid for doing exactly what I want to do.”

He was also one of two life vicepresidents of the Oxford University Tiddleywinks Society, the result of having squeezed the result of the annual Varsity match into the stop press column of the Oxford Mail at the expense of the 3.15 at Newbury.

The tie simply identified them as OUTS. “My wife,” said Arnold, “always supposed that there should have been an L in front.”

The risk, of course, was that it was he who offered me the chance to cut journalistic teeth, and at slightly more than 15 bob a week. “The chief sub-editor and the chief reporter went berserk,” he once recalled.

“They thought I’d finally lost my bloody marbles.”

YOUNGEST of a coke works fitter’s eight children, he was born in Spennymoor on January 6, 1929, attended what then was the Alderman Wraith Grammar School, edited the school magazine, was Durham County Boys Clubs’ cross country running champion and an enthusiastic boy scout with an enduring love of the outdoors.

Scouting tended to be sneered upon at Royal Marines training school, at least until the night on a snow-covered moor when Arnold’s group enjoyed hot coffee and sausages while others struggled vainly to light a fire.

It was when scouts and guides were encouraged to do more together – “We found ourselves forced to invite them to a Christmas party” – that he met Edna Spence, who became his wife for 50 years.

He never cared about respectability, he said. The only person he ever wanted to impress was Edna.

She died in 2004. “Dad had two options after that,” recalls Julie, his younger daughter. “He could have become a slightly eccentric recluse or he could have thrown himself heart and soul into village life.”

To no one’s surprise, he chose Plan B, joined the parish council, helped plant thousands of daffodils, became a tree warden (“It’s like The Archers round here,” says Julie) and despite walking with sticks while awaiting a knee replacement, joined the protest march that sought, unsuccessfully, to save the local post office.

The pub poker schools were perhaps predictable – he once won £60 and three skinned rabbits – the posthumous discovery of his bingo markers a little more surprising.

“Mum would have found it hard to believe that one,” says Julie. “It would just have been to support the Memorial Hall.”

Community commitment had been honed at the Spennymoor Settlement, an adult education centre formed in 1931.

“There are those in the town, still more beyond it, who mistakenly believe the Spennymoor Settlement to be some sort of alimony agreement,”

one or other of these columns once observed.

He was back in 2008 for the launch of the Settlement’s history, an occasion after which I’d rashly boasted in print that it was the first of two jobs on the same evening.

Arnold responded at once. “Every Monday I’d to pick up paragraphs in Crook, then all the villages to Tow Law and across to Wolsingham.

“In the evening I’d cover the film at the Tivoli in Spennymoor, get the bus to Coundon lane ends, run up to the dog track, collect the results, run back down to catch the next bus to Bishop Auckland, run to the office, write the crit and the dog results, run up to the station to put the copy on the train and run back to the market place for the last bus to Spennymoor.”

To the day of his death, last Thursday, he lost not a jot of his enthusiasm.

ARNOLD – “Once a Marine, always a Marine” – liked to say that he was posted to the intelligence section because he was the only one who could spell his name.

They armed the 19-year-old reporter with a pencil, a notebook and a sten gun and sent him to report the 1948 situation in Palestine. “There were enough incidents every day – bombings, shootings, killings – to fill half a dozen newspapers,” he once wrote, “and no news editor to say I was wet behind the ears. It was amazing how many stories you could get with a Sten gun.”

Demobbed, he completed journalistic training on the Echo, joined the Oxford Mail after the indelible impressions of Ruskin College and rose to deputy editor within nine years.

He’d also given a journalistic break to Jenny Joseph, whose poem “Warning” now adorns a million tea towels:

When I am an old woman I shall wear purple

With a red hat that doesn’t go,

and doesn’t suit me….

In 1964, he became editor of the Despatch, then the Northern Echo’s younger sister, where the editorial staffs were combined if not quite conjoined.

Arnold was determined that he should have a team of his own and the Despatch a new life of its own, that it should become a central player in the south Durham community.

He moved to Hurworth, formed the Community Association in the Grange – there’s still a Hadwin room – and launched the Friends of Darlington Civic Theatre. “We wanted a proper theatre, not a plaything for the aldermen,” he said.

He had offices on two floors, the upper echelon shared with Echo deputy editor Maurice Wedgwood.

Both were prodigious pipe men, the air blue no matter how civilised the discourse.

Arnold went on to edit the Bradford Telegraph and Argus and a large weekly newspaper group in Lincolnshire, the county in which he remained. He retired on his 60th birthday, rejoining the Labour party that he’d left on becoming an editor.

“He was never a revolutionary in the sense that he’d have people shot at the barricades, but he was an incredibly principled pragmatist,” says Julie.

“He always had a strong sense of the role of the local newspaper in the community and was quite proud of that tradition.

“Part of him was disappointed at what was happening to newspapers.

Money men had taken charge, not editors. Dad would always have wanted to fight his corner.”

He’d remained a prolific writer, too. The only problem, said Arnold, was that it was usually obituaries.

IN retirement he joined a voluntary group that taught journalists all over the world, cultivated both garden and grass roots, pursued hobbies like fishing, crossword compilation and stamp collecting, looked forward to the weekly visit of the Rington’s tea man, nurtured his grandchildren and was delighted at Christmas when Julie’s daughter announced that she, too, had won a place at Oxford.

He’d also produced newspapers to mark the youngsters’ visits. “I think they thought it was the fairies, but they still wrote letters to the editor,”

he said.

He became ill while on his way to a village hall committee meeting, thought it was something he’d eaten, was rushed to hospital and died a few hours later.

As well as the lucky-for-some bingo markers, they found a hare hanging – Arnold loved jugged hare, a Commando’s comfort at its excoriation and evisceration – and were obliged to ask around the village to restore it to its rightful owner.

The editor emeritus had last appeared hereabouts in October last year, consulted over the origins of the phrase “Tell it to the Marines.”

To it, said Arnold, should be appended “And they’ll get the job done, no matter what it takes.”

No matter what it took, he did.

Arnold’s funeral will be held at 1.30pm on Tuesday, February 1, at St Hugh’s church, Langworth, Lincolnshire, and afterwards at the Memorial Hall.

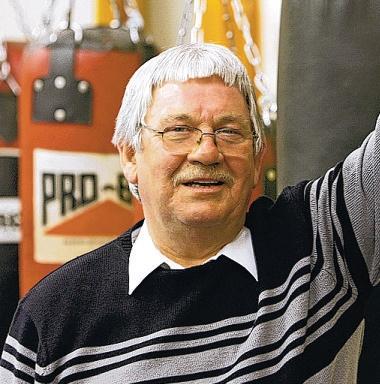

Still packing a punch

IT barely seems five minutes since we were attending our contemporaries’ 21st birthday parties.

Last Friday, back in Shildon and with his great grandbairns dancing attendance, it was Tommy Taylor’s 70th.

Great lad, Tommy – Durham County councillor for the Coundon area, former LibDem parliamentary candidate in Wales, amateur boxing champion and now chairman of Shildon Boxing Club.

He’s also been married four times, which promoted questions about the prospect of a fifth. “I need another wife like Custer needed more Indians,”

he said.

Back in 1974, when the future Lord Cobbold of Knebworth was Liberal parliamentary candidate in Bishop Auckland and Tom an enthusiastic campaign helper, the two had got on so well that Tom paid several weekend visits to Knebworth House, now reckoned one of the world’s great rock music venues.

The column had been a couple of times, too, those splendid occasions recalled by Lady Cobbold in her autobiography Boardroom in the Bath.

Mike Amos, she says, went on to become editor of The Northern Echo.

Always was a great girl, Chryssie Cobbold.

Now there’s talk of a nostalgic return to Knebworth in the spring, though the Cobbolds were unable to make the birthday bash at the Railway Institute. David, who’s 73 and has Parkinson’s disease, was whitewater canoeing on the Amazon.

SPEAKING of birthdays, last week’s column noted that Saltburn – by-the-Sea – is marking its 150th. Wholly coincidentally, both the Oldie the Guardian magazines devoted weekend pages to the dear old place.

In The Oldie, Candida Lycett Green – daughter of Sir John Betjeman whose parents inexplicably knew her as Wibz – is particularly impressed, enthusing over one the best beaches in the country, the “thrilling” water-balanced cliff lift, the “satisfactorily simple” pier, the solid Victorian terraces, the “robust, beautiful and peculiar” ironwork of the seafront balconies and the “galumphing” parish church.

Emmanuel church may never previously have been termed galumphing – wasn’t that Lewis Carroll’s beamish boy? – but no doubt it’s meant kindly.

The Guardian is only a little more circumspect – more admirers of the peerless pier, of the “nice shops” in Milton Street and of the “very charming” Ship Inn, almost on the beach.

The magazine also notes that in Henry Pease’s founding days, and for several generations thereafter, Saltburn wasn’t allowed pubs.

These days, it adds, there’s drinking and debauchery though it should be said that, on the day of the column’s visit, there was precious little of the first and absolutely none of the second. It was much too cold for debauchery.

SALTBURN’S first paying-passenger train is said to have steamed in on July 17, 1861.

The following month the first service ran on the South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway, that awesome track over Stainmore.

To mark the tercentenary, the Stainmore Railway Company – based at the reborn Kirkby Stephen East station – plans a weekend of events from August 27 to 29, the highlight of which will be the departure of the first passenger carrying train for 49 years.

It’ll be hauled, they hope, by 78018, one of the steam locomotives involved in the infamous Snow Drift at Bleath Gill. They’ll be showing the film, too.

Organisers also plan three major exhibitions on the history and impact of the railway from Barnard Castle to Tebay.

It’ll be opened on Saturday, August 27, by Stephen Davies, director of the National Railway Museum in York.

Details on their new website, stainmore150.co.uk AMONG the problems that have beset the good folk at Kirkby Stephen East is that many volunteers live on the County Durham side of the A66, barely passable for much of the past two months.

The snow has also caused problems for the station cat, known as Quaker doubtless because she’s black and white, though a snow tunnel has been dug to help her and a feeding rota arranged.

Already featured in the quarterly journal of the Cats’ Protection League – it’s called The Cat – Quaker’s real moment of glory will come in May when she’ll be visited by a chap writing a book on station moggies.

No such thing as telephone interviews, he’s coming from Japan.

CAROLLING before Christmas, we’d puzzled over a fiveword notice on the board at Newbiggin-in-Teesdale village hall.

“Say No to Article Four” it said.

On the assumption that it was nothing to do with Clause 4, and thus not in the nationalised interest, what on earth could it mean? John Niven in West Auckland and David Kelly in Mickleton both provide the answer.

It’s a provision of the Town and Country Planning Act which, depending on the view, either strengthens planning controls in conservation areas or endangers personal freedom.

It could, says Durham County Council, “maintain and enhance the special character of the area”.

They’re considering the same thing for Egglestone. No?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article