The centenary of a dreadful rail disaster in which twelve people died was marked with a special service at Hawes.

’Twas midnight at St Pancras As the Scotchman was due away, With a happy load of passengers Bound north for Christmas Day.

What greetings and handshakings, What talk of olden time.

“It’s handy man, glad to meet you Travel with us for Auld Lang Syne…” – John Thwaite

SHORTLY after 5am on Christmas Eve, 1910, the London to Glasgow train sped double-headed past Hawes Junction, where the Wensleydale branch of the North Eastern Railway met the Settle and Carlisle line, and the Midland.

The Helm wind whipped across the high fell, the rain slashed against the windows of the box where signalman Albert Sutton was nearing the end of a ten-hour night shift made busier yet by the extra trains ferrying folk felicitously towards their families.

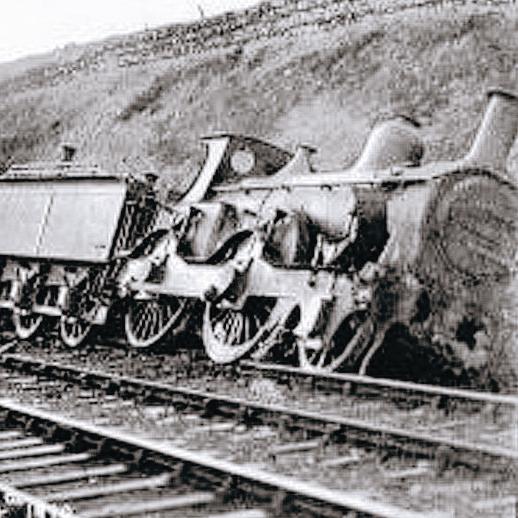

Simpson, the relief man, was already in the box when Sutton realised that he had made a terrible mistake. Two light engines, coupled together and heading north towards Carlisle, had been allowed onto the main line just ahead of the fast train and on the same section of track.

Twelve people, including a little girl, died in the collision and inferno that followed. Sutton’s instruction to Simpson is still chillingly recalled: “Go tell Bunce (the station master) that I am afraid I have wrecked the Scotch Express.”

The centenary of that Christmas Eve disaster was marked last Sunday with a special service at St Margaret’s church in Hawes, signalman Sutton’s great grandson and his family among those present.

It was led by Canon Bill Greetham and by the Reverend Ann Chapman, vicar of Hawes. “I felt that its being Christmas gave some meaning to the tragedy,” says Canon Greetham.

“It means that there is still hope.

The birth of Jesus brings hope to the world.”

COINCIDENTALLY, some might suppose ironically, there was a shepherd in the story, too. Albert Ashton, who lived on the moor near Shotbolt tunnel, was starting his day when he heard nearby the sound of an horrific impact.

The Board of Trade inquiry timed it at 5.19am.

“Darkness still enveloped the countryside and the rain was falling smartly,” Ashton told The Northern Echo.

Some of the injured from the wreck of the Christmas Eve express were taken to his isolated cottage; Ashton remained behind to try to rescue those trapped in the front two carriages – gas-lit, wooden – that had telescoped into the light engines ahead.

Others joined the attempt, until the gas ignited and soon, he said, they were beaten off by the flames.

“We had done our best to rescue two men who were still alive, but both perished in the conflagration.

Very soon, the whole train was on fire.”

One of the victims was John Stitt, returning to Scotland. His last words, no less poignant than signalman Sutton’s anguished realisation, are engraved at the foot of a memorial in Hawes churchyard.

“Oh! Tell my mother about this, will you? She lives in Ayr.”

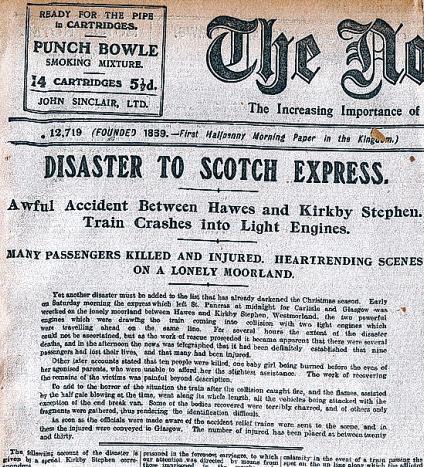

ALMOST the whole of the Echo’s broadsheet front page on Boxing Day, 1910, was taken up with the “great calamity”

near Hawes. “Yet another disaster that must be added to the list that has already darkened the Christmas season,” we said.

Many of the injured had been put on another train to Glasgow, desperate relatives waiting at the station.

In the other direction, a special train brought family – “a group of sorrowing, despairing men and women whose errand was to ascertain beyond any doubt the fate of their unfortunate kinsfolk.”

Christmas Eve or not, Christmas Day or not, hordes of what the Echo termed “visitors” – there are other words – had also been drawn to the scene.

“Scores of cycles were piled against the adjacent fence walls and numerous motor cars were dotted about the roadway,” we reported.

The bodies, such as remained of them, had been taken the mile-anda- half to the Moorcock Inn, near what now is Garsdale station, but then was Hawes Junction.

Led by Major Pringle, the Board of Trade inquiry began at 9am on Boxing Day at the station, the inquest opening at the Moorcock four hours later. The bodies were in the next room.

More than a score of press men crowded the pub’s front parlour, the coroner willing only to allow four of them into the hearing. “I was one of the lucky ones,” wrote the Echo’s correspondent, rather macabrely.

Major Pringle’s report spoke of a violent collision, of fire that spread through the train, of bodies “completely or partially destroyed”.

It recommended safer signalling systems that already had been introduced on other companies’ lines, intended to prevent two trains ever again being on the same section of track.

While poor Sutton’s “lapse of memory” could not be excused, Pringle was also critical of the light engine drivers who’d broken a “frequently disregarded” rule by not whistling to draw attention to themselves while waiting more than two or three minutes for the signal.

The ten-hour shift, he concluded, had played no part in the tragedy.

CANON Greetham, a former vicar of Patrick Brompton and surrounding villages near Bedale, now lives in retirement near Carnforth and is a volunteer guide on the Settle and Carlisle Railway.

Sunday’s service, it had been suggested, might fall victim to the snow.

“There was never any doubt in our minds that it would go ahead, though the numbers were lower than they’d otherwise have been,” he says.

“Men worked through hell and high water to build this railway and to keep it going. We weren’t going to be beaten by a few flakes of snow.”

The service proved emotional, not least because of the presence of Peter Sutton and his family. “I have a lot of sympathy for Albert Sutton, he must have been under a lot of pressure that night,” says Canon Greetham.

“The night was perfectly foul and he had no fewer than nine light engines sitting there at Hawes Junction.

There’d been 58 trains during his shift, probably more than normal because people were trying to get home for Christmas. That’s an awful lot. He must have been very weary.”

They heard a reading of the late John Thwaite’s 17-verse poem about the accident, a recording of Kit Calvert – another fondly remembered dalesman – recalling how his father, a quarryman, had seen the Christmas Eve blaze and thought it must be a haystack alight.

Afterwards the “rather neglected”

memorial to five of the dead was rededicated after the Friends of the Settle and Carlisle Line had raised £500 for the work.

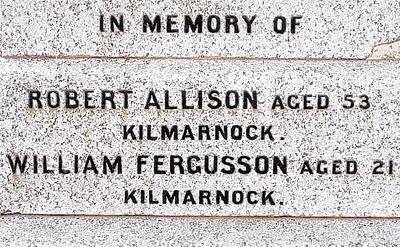

Almost three years after the wreck of the Scotch Express, September 2 1913, 14 people were killed when two trains collided at Ais Gill, just a couple of miles away. There’s a memorial in Kirkby Stephen churchyard, where Canon Greetham was once vicar.

“I’ve no doubt that in three years time we’ll be doing something pretty similar there,” he says, “but at least, of all the times of year, it didn’t happen on Christmas Eve.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here