RON JOHNSTON was a shipyard plater’s son from Hartlepool – old Hartlepool, proud of it – when a routine tooth extraction went horribly wrong.

His mouth and eyes bled for five days. An optic nerve had been damaged, leaving him blind. It was 1929; he was five.

Handicap notwithstanding, Ron became a councillor in Bishop Auckland, was founder chairman of the St Helen’s and Tindale Crescent community association, masterminded the building of the community centre and beat 500 applicants to become north regional director for Oxfam, a role in which he inspired thousands and helped millions.

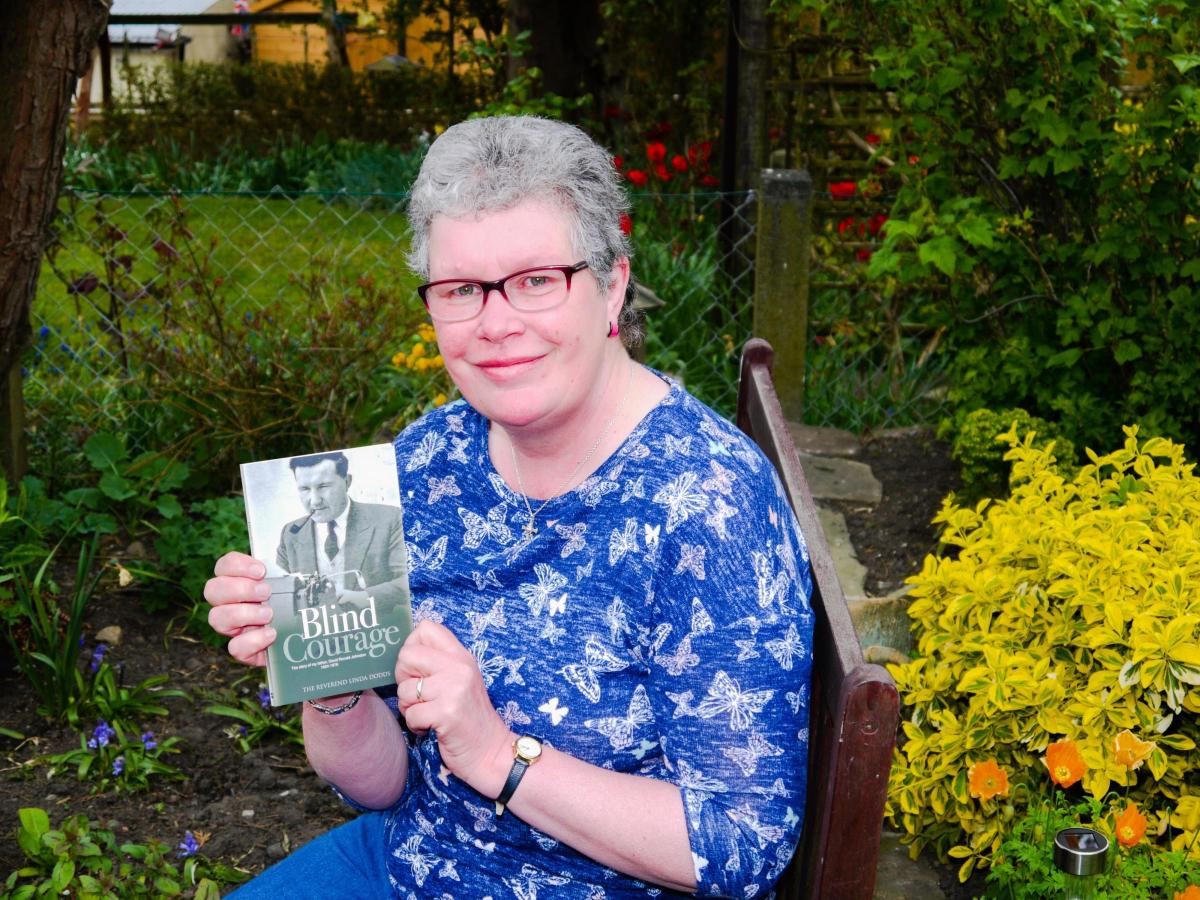

His remarkable story is told in a new book by the Rev Linda Dodds, his daughter. It’s simply called Blind Courage.

“My dad had this remarkable ability to visualise. Whether it was where he was or what he wanted to do, he could see things clearly in his head,” she says. “He also had an amazing, encyclopaedic memory.

“He could have sat back and let people look after him, but that was never my dad. He always said that he’d rather be blind than deaf because being deaf left you isolated. I hope parts of the book will make people laugh, but it’ll make them cry, too. He touched many people’s lives.”

The little boy was sent almost immediately to a residential school for the blind in Newcastle. Partly it was to learn independence, says Linda, partly because they weren’t really expected to learn much at all.

Thereafter he went to the Royal Normal College, interestingly named, in London, declining dog, white stick or even linked arms. Sometimes he’d use slight shoulder contact, others he just knew his way around.

He gained top shorthand (140 words a minute) and typing awards, challenged the sighted. “The only difference was that he couldn’t rub out his mistakes,” says Linda. “Happily, he didn’t make any.”

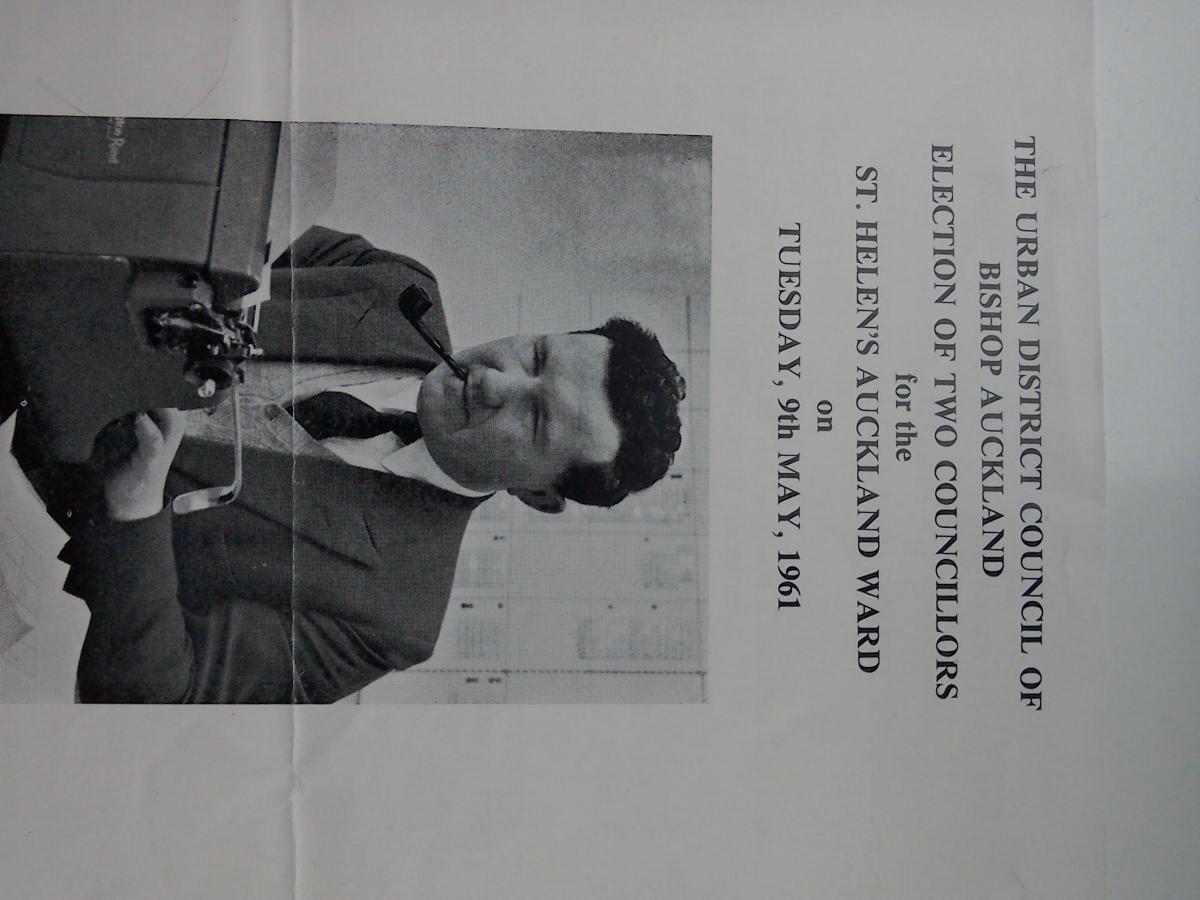

He became a telephonist at a Bishop Auckland factory (“it was what blind people did”), then a secretary elsewhere. In 1961 he was elected an Independent councillor – “not for or against any party,” said the literature, “just anxious to help".

His first municipal assignment was to inspect Binchester sewerage works. “Just the job for a blind man,” says Linda.

He met Doreen, his future wife, when she delivered door-to-door for the London and Newcastle Tea Company. Ron liked the sound of her voice. “My mam was beside him in everything, she was his enabler, had to forget that she was really quite shy.”

The Oxfam job began in the spare bedroom, Doreen his unpaid secretary, inevitable expansion accelerated when a new baby claimed the room. Regional offices were established just off Bishop Auckland main street, the patch – and the need – ever-growing. By then he had a guide dog, as familiar as his pipe, his trilby hat and his brief case.

Famine in Biafra and in Ethiopia – “the first time pictures of starving people were in everyone’s front room” – increased both demand and effort.

“He had a real heart for the poor,” says Linda. “Partly he wanted to do the job to prove that he couldn’t just be someone’s secretary, but he cared passionately about those less well off than himself.

“He travelled all over the north and beyond, often by bus and train, setting up committees, enthusing people. We were always raising money for things, or collecting silver paper for guide dogs.”

Though never one to feel sorry for himself – “his only regret was that he couldn’t drive, he loved cars” – Ron became ill in 1975 and died, aged just 51, the following year. He was one of the most amazing men I ever met.

“It was called a breakdown then, today we’d call it depression,” says Linda. “For the first time in his life he turned inwards. It was hard for us to convince him that he was safe; the darkness overcame him.”

Linda was a librarian, became a Church of England priest, lives in Etherley, a few miles above Bishop Auckland, got the idea for her father’s life story from a friend. “What started out as a few notes for the family quickly became a book.”

It’s published on June 5, launched on June 12 (7pm) at an event in Bishop Auckland town hall to which all are welcome. The book’s published by Memoirs Publishing, is available (£12.99) on Amazon or contact Linda at reverend.linda@yahoo.co.uk

BACK in the 1970s, Bernard Hall was an economics lecturer at Durham University and wrote occasional pieces for The Northern Echo. “As a young man I was going to be the next Tolstoy,” he recalls. “I ended up doing bits for the Echo.”

Our paths have crossed before. I’d mentioned him back then, “promoted” him to professor – “much to the chagrin of my more ambitious colleagues” – had to carry a correction.

Chair pulled from under him, Bernard joined Durham County Council in the 1980s, became a social worker covering Spennymoor and Shildon, hoped to make the world – or that blessed part of it – a happier place.

It’s that which is the background for his first novel, Miss Perfect. Durham County Council becomes Rudham – clever, eh? – Spennymoor is Moortown and Shildon, less obviously, Brownlow.

It’s in Brownlow that he swears he encountered the fabled council house horse, the one that lived in the back bedroom. (Others swear it was Woodhouse Close.)

Madge Perfect, that name also changed, was one of his gaffers, a single woman in her 50s with a heart for the job and for her social service clients.

Others in the department were more concerned about stabbing her in the back. Rudham, says Bernard, had “an ageist and very sexist culture”.

The book’s wry, amusing, perceptive, insightful and greatly entertaining. There’s much to which both town and gown will relate, though the Golden Slipper massage parlour surely couldn’t have been in Shildon.

Bernard’s now 78, lives on the south coast, swears he’s trying to tunnel northwards. On July 1 he hopes to be signing books at Waterstone’s in Durham; at 7pm on July 6 he’s addressing the Local History Society in Shildon Methodist church hall. Or Brownlow, as the case may be.

RICHARD GAUNT’S picture albums have featured here before: photographic songs of the sixties recorded during his Darlington schooldays and gap year employment at ICI Wilton.

The latest, with carefully crafted narrative, reflects the subsequent years at Cambridge, mellifluously monochrome but, much to his regret, shorn of the steam engines upon which his Exacta had so often focused back home.

Darlington and Cambridge were much of a size, both with rivers. “It has to be said,” Richard supposes, “that the Skerne in the 60s was much more likely to feature old prams and oil drums. So far as I’m aware, there was also no recreational punting tradition in Darlington.”

The Skerne, he adds, presents a very much prettier picture now.

Initially he read natural sciences – the ICI lab coat impressed the unworldly – switched to economics, the degree ultimately upgraded to MA “after paying, as I recall, two guineas”.

Much water has flowed down the Cam since then. An undergraduate’s study, the book captures magnificently the way that things were.

- In and Around Cambridge in the 1960s by Richard Gaunt (Fonthill Media, £18 99.) Also available as an ebook.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here