THIS is my favourite gooseberry-related story of all time. It gets a mention in Saturday's Memories (15/12/12), but here it is in its entirety which, when I told it in 2001, was so enormous that it spread over two weeks.

The sad footnote to the story is that the prized herbarium, enthused over by the professor of botany in 2001, was lost when I enquired of Tyne and Wear Museums about it in 2011.

I wonder if the downy currant still grows at Richmond and on the banks of the Tees between Piercebridge and Gainford...

=========================

Finding true-love in the language of plants

The Northern Echo 03/10/2001

IN Darlington, the Robson family were noted as linen weavers. They had a business on Northgate, and the River Skerne behind their shop helped them to create their cloth.

But further afield, the Darlington Robsons were noted as botanists, with two of them being considered the most significant plant collectors of their generations. One of them even had a gooseberry named after him.

The first of the Darlington Robsons was called Stephen. He was born in Northgate - roughly where the ring-road roundabout is today - on June 13, 1741. He received a basic Quaker education and also, through long country walks, fell in love with nature.

He made contact with the Newcastle botanist and mathematician Robert Harrison (1715-1802). As well as being older, Harrison was better educated and connected than the humble linen-worker in Darlington. The pair exchanged seeds, rootstocks and specimens, and through Harrison, Stephen became acquainted with the professor of botany at Edinburgh University. At first, Stephen was asking the professor questions; later, the professor was turning to Stephen for help.

As his reputation grew, Stephen contacted William Curtis, the most respected botanist of his generation. Curtis advised Stephen to start keeping dried specimens of his plants.

At about the same time, Stephen's father Thomas (1691-1771) died and Stephen inherited the Northgate linen business. He set about his new tasks with gusto: he added a grocery shop to the linen business, and began drying plants.

During 1772-73, he dried 320 species of flowering plants and 340 specimens of ferns, mosses and fungi. From 1774-78, he collected another 244 specimens which he had missed in his earlier rambles.

These dried plants formed the three volumes of his Hortus Siccus - a manuscript that is now in the hands of his great-great-great-grandson in Preston. In 1777, Stephen produced a printed version of Hortus Siccus (Latin for dried plants), which he called The British Flora.

It sold for five shillings and did not zoom to the top of the bestsellers list, but is now regarded as a "significant contribution to botanical literature".

"It didn't achieve great fame, but it was at the time an important work because it was one of the first floras to be published in English," says Professor Peter Davis, head of the archaeology department at Newcastle University.

A Victorian historian wrote that, because of the business and family calls upon Stephen's time, the British Flora was "published when the enthusiastic author was only 36 old and closely confined to the counter, (it is) however, no mean attempt for one entirely self-taught as regards the classic languages and science, and reflects great credit upon his proficiency, and the good purpose of which this was applied".

Stephen's was the earliest attempt in English to organise plants into their proper families - before, botanists had stuck to lengthy Latin names while ordinary people had wandered the woods using English names.

For example, botanists knew a woodland plant as Paris quadrifolia while from Stephen's work we learn that 18th Century English people called it either "true-love" or "one-berry". Today, if we could find it, we'd know it as Herb paris.

Almost immediately after his great triumph, Stephen died. Another Victorian historian wrote: "He did not long survive the publication of the Flora, being carried off by pulmonary consumption in his 39th year. Naturally of a delicate constitution, there can be little doubt that his severe studies, and the too sedentary occupation of leisure from business, hastened his premature and greatly regretted decline."

PART TWO:

Last week, Echo Memories told of Stephen Robson (1736-1812), of Northgate, who was the first man to write a book of flora in the English language. Stephen's love of botany passed along his family tree to his nephew Edward (1763-1813).

Also born in Northgate, Edward was "one of the most active English botanists of his generation". In 1790, he produced a 270-page Supplement to his uncle's Flora, but his piece de resistance came in 1793: Plantae variores agro dunelmensi indigenae (Rare plants native to Durham).

This exhaustive list was presented to the Darlington National History Society, a society that folded in the mid-19th Century. In 1891, the Darlington and Teesdale Naturalists' Field Club was formed, and took over the earlier society's archives - including Edward's list.

It is written in Latin, except for an addendum at the back. "Since our last meeting," Edward writes, "other rare plants have come to notice: ophrys insectifera (fly orchid) in a wood near Middleton One Row which I suspect is the same place where my late uncle Stephen found it in 1777. Ophrys apifeso (bee orchid) in Baydales near Darlington and, in the same place, is thalictrum which I take to be the vibirium." Thalictrum, according to Cliff Evans, the general secretary of the Naturalists' Field Society, is some form of meadow rue.

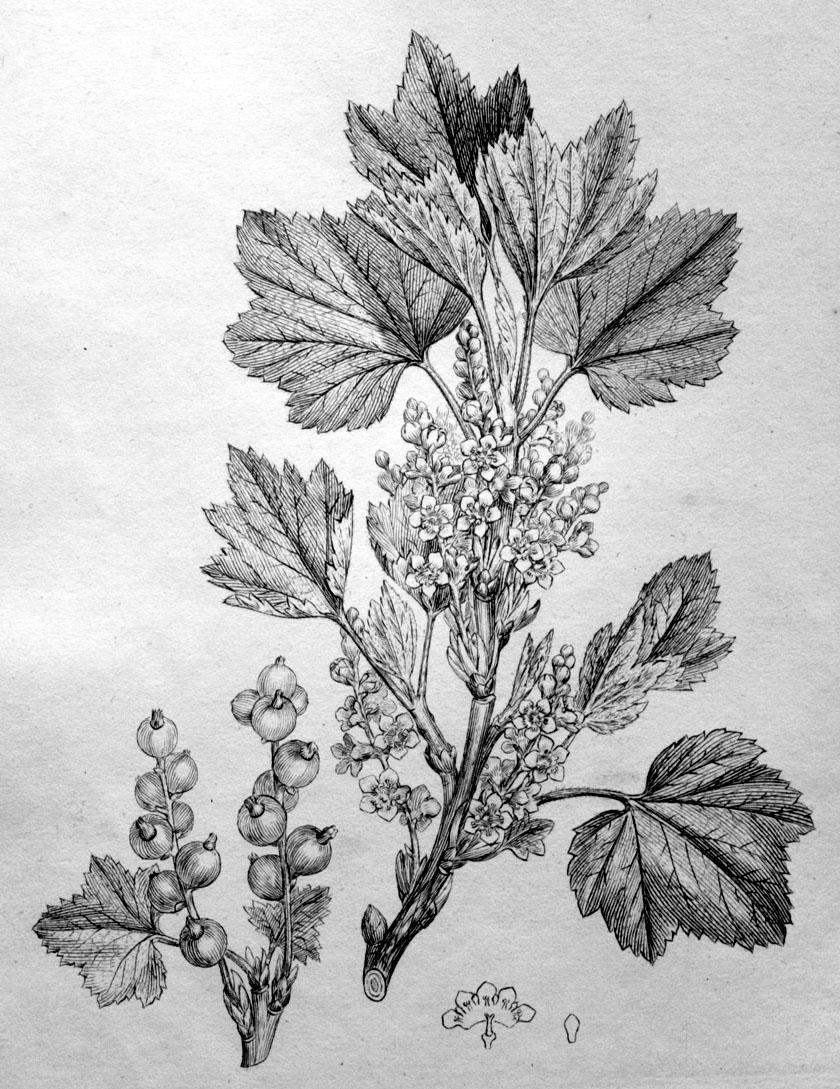

The manuscript also includes a pains-taken drawing of Edward's greatest find: the ribes spicatum, or Downy Currant. It is a redcurrant covered in fine hair, native to Yorkshire and Durham, that had never been identified before.

Edward said of its discovery: "The dried ones were taken from a tree which was brought from the neighbourhood of Richmond in Yorkshire some years ago to my late uncle Stephen Robson who planted it in his garden where it remained for several years."

So famous did Edward become that after his death in 1813, a family of gooseberries was named after him (the gooseberry belongs to the same family as the redcurrant that Edward discovered). Robsonia gooseberries are to be found in the west of North America. The Robsons' reputation fell fallow in the early part of the 20th Century, but Edward's was repaired in the early-1980s when Sunderland Museum discovered that it had his herbarium - a collection of dried flowers.

"There aren't many herbariums dating from the 1790s," says Professor Peter Davis, who discovered Edward's work and who is now head of archaeology at Newcastle University.

"The heyday of the plant collector was in the 1840s and 1850s when natural history became a social pursuit and that makes Edward's early work very interesting.

"He was obviously interested in self-improvement but being a strict Quaker, things like music, dancing or theatre were not open to him. But country walks were and he became interested in botanical fieldwork. He collected plants throughout the north of England and was one of the earliest explorers in upper Teesdale."

Cliff Evans, of the Darlington and Teesdale Naturalists' Field Club, says: "In upper Teesdale there are arctic and alpine types of plants that really shouldn't be there. It is a very special selection, known as the Teesdale assemblage, the best known of which is the spring gentian. Teesdale is the only place in mainland Britain where it can be found."

In Edward's day in the 1790s, south Durham was a very different place to today. It was all agriculture, horsepower, hay meadows and wilderness.

"Edward would have been able to walk out from Darlington and soon be in relatively wild and exciting places," says Prof Davis, "but I suspect the rare plants he would have been able to find after ten or 20 minutes walking have now gone."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here