Some of the most significant Northern impressionist paintings, capturing life on the coast in the early 1900s, are sitting in art gallery vaults. Ruth Campbell talks to an expert who hopes to get them back on display.

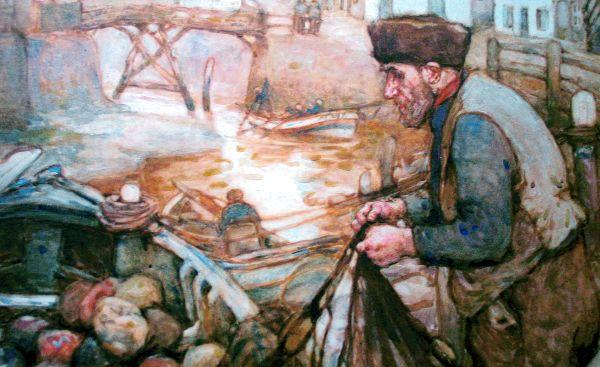

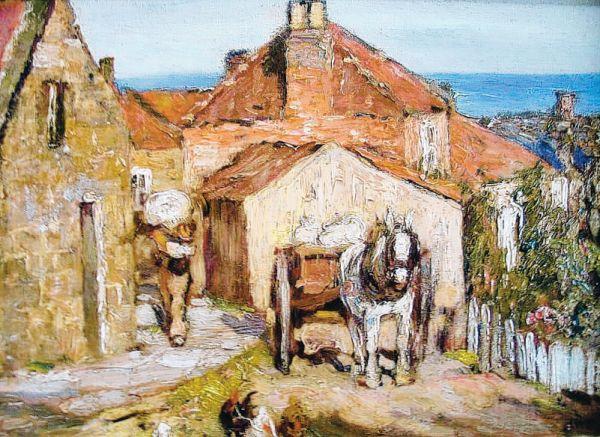

THERE is something about the quality of the light and the broad, confident brush strokes. The images, of huddled, storm-battered cottages, wild seas, towering cliffs and resilient, hardy locals, are unmistakable. The mood of these atmospheric paintings, set in the wild and beautiful landscape of the North Yorkshire coast and moors, still strikes a chord today.

Yet, many of these Northern impressionist works, created by the influential Staithes Group of about 35 artists back in the early 1900s, lie, inexplicably, hidden in gallery vaults.

Art expert Rosamund Jordan is determined to change that. She is urging us all to protest and demand that works by this world-renowned group of painters, who were based in and around the tiny fishing village of Staithes and played an important role in the development of British Art at the turn of the 20th Century, are hung on gallery walls again, for us all to enjoy.

“Too many galleries prefer to exhibit things like till receipts from Morrisons at the moment,” says Rosamund, who is convinced there is an anti-North-East bias in the art world.

Apart from the Pannett Art Gallery, in Whitby, there are few venues where the public can enjoy the Staithes Group works. “From Glasgow’s museums to London’s Tate, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Imperial War Museum, all major galleries have Staithes Group works in their collections, but they are rarely displayed,” says Rosamund.

And what we are missing out on are paintings by artists such as Dame Laura Knight, official war artist at the Nuremberg trials and widely regarded as one of Britain’s greatest female painters. Internationally- renowned landscape artist Arthur Friedenson has also been consigned to the gallery cellars.

“Winston Churchill reckoned Friedenson’s skies were second only to Constable, although I think they are better. I think he developed into the best landscape artist there has ever been,” says Rosamund.

‘THE Staithes Group are all incredibly good artists, inspired by Monet, Cezanne and Renoir. Many of them studied in Paris alongside the well-known Glasgow Boys and the Newlyn School of artists, all of them exhibited at the Royal Academy at the same time. But the Staithes Group is still never included on anything written or distributed on British art.

I think it’s because they are from the North-East,” says Rosamund.

“When people go to any major gallery, they should ask if there are any Staithes Group pictures in the collection and, if so, ask why they are not on show. People should ask to see them and register their disappointment at the fact they are not put on public display,” she says. “I do it myself and am now urging others to do the same.”

Rosamund, a former art teacher from Stockton who is now a collector and dealer, was first drawn to these particular paintings in the early Seventies, before they had even been clearly identified as a distinctive group. She began collecting them after an aunt left her some uninspiring Victorian oil paintings. “I decided to sell them and get some I liked,”

she says.

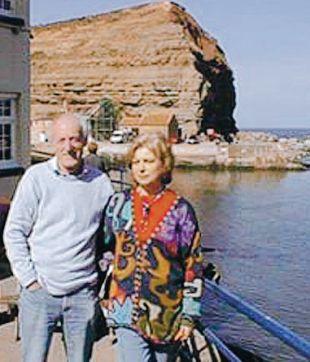

At the time, the Staithes artists hadn’t been identified as a group and were simply described as Northern impressionist painters. Rosamund and her geography teacher husband, Tom, who divide their time between their home outside Teesside and a cottage in the village of Staithes, bought about half a dozen works.

Rosamund loved the light and atmosphere of the paintings which captured the coast and fishing communities, moorland landscape and farms of the local area they loved.

“They painted in a free-flowing, impressionist manner, with vibrant colours and broad brush strokes, but the greatest influence on all these artists was the area itself. The light in this part of the world is fantastic, the mood and the colours of the sky and the sea always changing.”

IT is not hard to see why the tiny, thriving fishing village of Staithes, with its picturesque huddle of cottages, wild seas and expansive moorland backdrop, became a powerful magnet for artists back then. They sought to record working people going about their daily tasks and the hardy locals provided a constant source of inspiration.

The paintings show catches being unloaded, gutted or sold, children playing on the beach and women knitting ganseys, or carrying baskets of mussels on their heads over the foreshore. Boats were pictured being dragged up and down the beach where, in rough weather, the atmosphere could suddenly change from happiness to tragedy.

“Go to Staithes,” the young Laura Knight’s drawing master had urged her. “There is no place like it in all the world for painting.” Countless other artists agreed. Staithes had already been home to the “Turner of the North” George Weatherill and other towering figures of the 19th Century art world.

The coming of the railway, in 1883, brought yet more artists to the village and surrounding area, including Laura’s husband, Harold Knight, Robert and Isa Jobling, and Arthur Friedenson, many of whom had lived and trained in Paris at the height of the Impressionist movement.

Rosamund, who regularly gives lectures on the Staithes group now, says there was a real sense of empathy with the local community.

“Many lodged with fishing families and, although I don’t think they really socialised with each other, they were so in tune with the people living there. They were able to capture the life, and how hard it could be, so well,” she says.

As Rosamund and Tom’s Staithes Group collection grew, more and more people started to show interest and they decided to go into the art business full time in 1974, opening a gallery in Yarm and holding increasingly popular one-day exhibitions: “We had too many pictures and couldn’t afford to buy any more until we sold some,” she says.

Demand increased in the mid- Eighties when artists painting in the area during the most productive years of 1901-07 were firmly identified as the Staithes Group.

Initially, most paintings were sold outside Yorkshire, to the States and other parts of the country, although now there is much more local interest in everything from sketches, costing from about £90 to Laura Knight paintings, priced at up to £30,000.

“People like the idea of investing in their own cultural heritage,” says Rosamund.

Although there are favourites they will never part with – including two Friedensen’s which hang on their walls at home – Rosamund and Tom have now sold about 2,000 paintings.

“They are not one-off wall decorations.

Collectors come back again and again. It’s something safe to put money in, as well as to enjoy,” she says.

The Staithes Group started to disintegrate around 1907, when many were drawn south in search of fresh horizons. For some of those who left, it was a tremendous wrench.

“Staithes had been one of the most vital influences in my life,” said Laura Knight. “I hated leaving the moorland and the North Sea, the struggle that made you strong, the wild race of fisher people I loved so well.”

But their legacy continues even today, as countless other artists have gone on to find inspiration in the village’s huddled cottages, jumbled roofs and wild seas. Lilian Colburn came to live in Staithes “to save my artistic soul” later in the 20th Century.

And celebrated painters Eric Taylor and Fred Williams also settled here. Len Tabner paints from his studio on the cliffs at Boulby. David Curtis has a cottage in the village, as does Melissa Cotter.

Rosamund and Tom, whose daughter and granddaughter live in the village, come every week. “I walk down the top of the slipway in Staithes and the tension strips off.

The light, the sea and the sky – every time we go there it looks completely different. It is such a special place.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article