Paula Knight's graphic novel draws on what it means to be a women, and a mother – or not. The writer, who grew up near Darlington, explains how it's a mirror of her own life

I grew up in Hurworth, County Durham, in the 1970s and 80s. My lasting memories are of boiling hot summers playing out, and winters with snowdrifts deeper than I was tall. My best friend and I played in Hurworth Grange Community Centre grounds, where we were feral, climbing trees and hanging around the swings listening to older girls gossip about the facts of life. It was a fairly traditional upbringing, with the rest of my family close by in Darlington.

I could not have wanted for a better grounding in art education than I had in the North-East. Hurworth Comprehensive School’s art department, headed by the dedicated Brenda Swinney, was excellent, and I consider myself lucky to have been taught by her. This is where I learnt to draw, or rather ‘paint with a pencil’ as was her oft-repeated mantra. Her infectious enthusiasm instilled the interest and confidence to believe I could choose a career in art one day. A small group of us also attended a photography course at Darlington Media Group, which led to me showing work in an exhibition for the first time. I studied A Level Art, English, and French, at Queen Elizabeth Sixth Form. The art department at that time was situated nearby in a building called Claremont, which offered the cosy informal ambience of a mini art college – it gave me a taste for life as an art student. I studied Foundation in Art & Design at CCAD in Middlesbrough, going on to apply for Graphic Design degree courses.

My parents had friends just over the River Tees in Croft, where Lewis Carroll’s father had been the rector of Croft church. Their son’s fantastic ink drawings adorned the walls of ‘Alice House’. He had copied them from Sir John Tenniel’s illustrations in Alice in Wonderland. This inspired me to buy ink pens, and I also set about diligently copying Alice drawings (and Paddington Bear). I revisited pen and ink again when my interest in comics and graphic novels grew.

As a teenager, I hoped that being an artist might involve a glamorous life designing edgy album covers for bands like Iron Maiden. For me, the opposite was true – my first paid illustration work was for cute greetings cards. I later worked as a children’s illustrator for many years before embarking on my graphic novel, which is all about not having children, and very much for adults! My interest in graphic novels grew when I discovered that there were other middle-aged women writing autobiographical material in this medium. This happened to coincide with the time in my life when I was trying for children.

The 1970s and 80s were a unique era in which to grow up female. The expectation was still that you’d get married and have children, but, over that period, more and more women were applying to universities and going back to work after having children. I wanted to enter higher education and forge a career, too. With women’s magazines suggesting that I’d be able to ‘have it all’, that’s what I expected to happen.

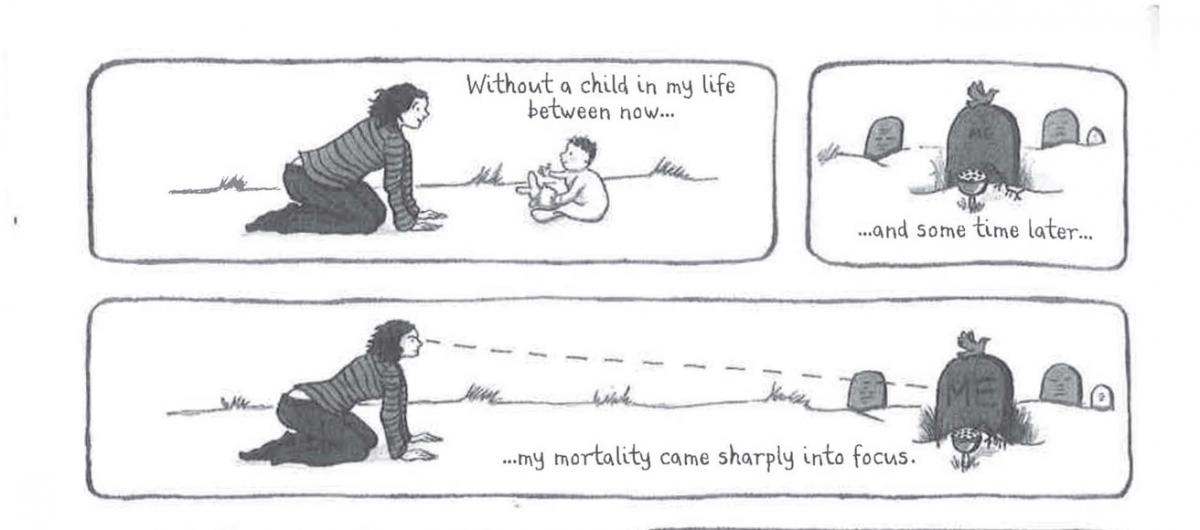

My partner and I tried for children for three years in our mid-thirties. I had three early miscarriages, and was diagnosed with ‘unexplained recurrent miscarriage’. There was no treatment at that time, although I’m pleased to learn that research into early miscarriage is well under way. My general health had also declined, and I was diagnosed with ME/CFS (chronic fatigue syndrome). At the age of 40, with no guarantee of being able to carry a pregnancy to term and my levels of fatigue so debilitating, we made a tough decision to cease pursuing parenthood. Two conditions with little hope of any imminent cure made our future too uncertain to be confident about the prospect of pregnancy or childrearing.

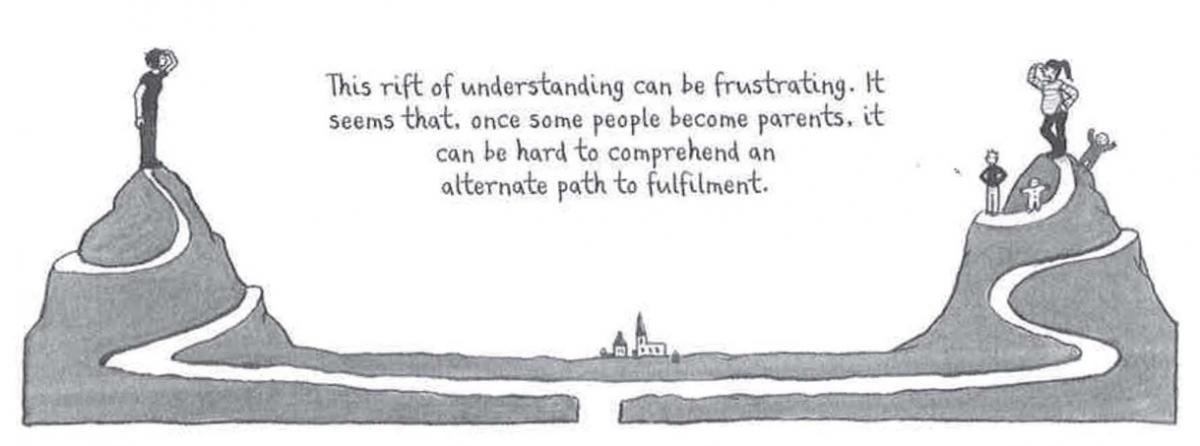

I eventually found some comfort in dealing with this through drawing comic strips about my experiences, and sharing the work online. The response I had was very connecting, and women thanked me for expressing something they felt unable to say. My memoir expands on that work and explores the pressures on girls to become mothers, and what happens when life doesn’t go to plan. Part one is set in the North-East and is about the family, social and cultural cues which informed our knowledge and expectations. Top of the Pops, EastEnders and Jackie magazine all played their part. My hope is that the book will offer comfort to those who couldn’t have children, as well as highlighting some of the many complex reasons why one in five women of my generation didn’t reproduce.

I’m certain that my schooling paved the way for being able to handle such a labour-intensive project; it took me almost six years to complete. You can take the girl out of the North-East, but you’ll never erase the art education she had there.

- Paula's graphic novel, The Facts of Life, is published by Myriad (£16.99).

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here