Some of the best Egyptian museum collections are on display in the North, says Egyptologist Joann Fletcher. She tells Ruth Campbell how this ancient people got under her skin

JOANN Fletcher wanted to be an Egyptologist from the age of six, when she was inspired by seeing the Tutankhamun exhibition in London, complete with the iconic golden death mask. But when she mentioned this to the careers department at secondary school, the idea was regarded as laughable. “Don’t be silly, you can’t be an Egyptologist, you’re from Barnsley,” she was told.

Prof Fletcher, who went on to become one of the country’s leading experts on ancient Egypt, the maker of a number of award-winning documentaries and the author of nine books, including the acclaimed Search for Nefertiti, had the last laugh. Particularly when a hoard of 2,000-year-old silver coins minted by Mark Antony and Cleopatra to pay their troops at the height of their love affair was discovered in her home town of Barnsley.

Prof Fletcher, whose latest book The Story of Egypt, is the culmination of a lifetime of research, argues that some of the best ancient Egyptian museum collections in Northern Europe are in the North of England, with one of the finest in Harrogate. And she points out that the study of Egyptology in the UK actually began in Yorkshire when George Sandys, the youngest son of the Archbishop of York, set off on a grand tour of Europe back in 1610. “He was both learned and wealthy, a brilliant man, and wrote an account of his tour, describing pyramids, mummies and royal tombs," she says. “This Yorkshire lad marked the beginning of England’s interest in ancient Egypt and it’s a tradition I’m proud to continue. I feel as if I am standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Until recently, many ancient Egyptian treasures, donated to the public by generous benefactors and collectors in the 19th century, have lain in storage in municipal museums in the North. “Children from here used to have to get on a train, which was expensive, to get to the British Museum to see things, as if this was a subject only to be enjoyed in London and the South-East. But things have changed.”

Prof Fletcher, who works closely with a number of Northern museums, has been instrumental in ensuring more Egyptian artefacts are put on public view. “Kids can now just go down the road and see some fantastic collections in local displays," she says.

Harrogate’s famous gold and black Anubis mask, worn by a priest during embalming and donated to the public by a local collector, is so highly prized it was briefly loaned for display at the Victoria and Albert museum. “It is now the jewel in the crown of the Pump Room Museum collection,” says Prof Fletcher.

The collection also includes amulets, jewellery and a gold death mask donated by the family of jeweller James Ogden, an advisor on the gold work in Tutankhamun’s tomb in the 1920s. “A mask for the living and a mask for the dead, it’s a magic combination.”

Prof Fletcher is based at the University of York and lives on the North Yorkshire coast. Although her work takes her all over the world, including cross cultural studies in the Yemen, Sudan and Greece as well as to Egypt itself, she would never live anywhere else. “I have always loved the sea, I find it inspirational and relaxing. We came to Scarborough on holiday as a child. I even picked out the house and, as luck would have it, it came up for sale.”

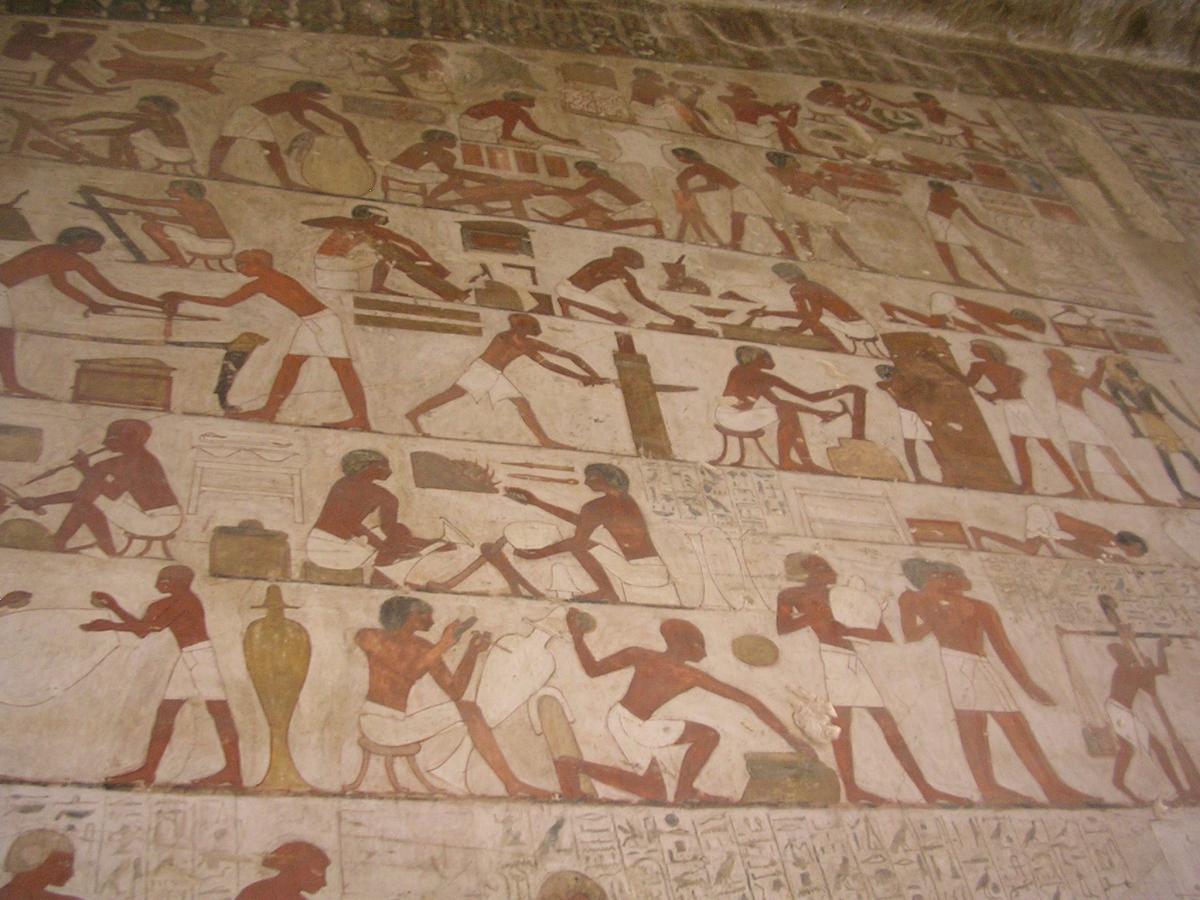

What is so refreshing about her latest book, which spans more than 4,000 years of history, from the first pre-dynastic settlements along the banks of the Nile up to the time of Cleopatra, is that it is not dry or academic. Down-to-earth Prof Fletcher tells the story of ancient Egypt in her own words, examining how ordinary people lived and worked. And she really brings the characters to life. “The ancient Egyptians weren’t the weird, animal-worshipping, strange human beings, walking sideways and a bit exotic, which so many people think of, with no relevance now. They were people just like us.”

She goes beyond the male elite of kings and priests who so often form the basis of ancient Egyptian studies. “I wanted to look at the people who built the pyramids, the grafters and the workers, to focus on where they lived and slept, what they ate and drank and how they gave birth.”

Ordinary women, so often ignored, come under scrutiny and the professor's study of women’s hairstyles has thrown up new ideas. “Metal pins were sharp enough to pierce skin. They could be lethal. A woman could be apparently unarmed when walking down the street, then whip her hairpin out and job done,” says Dr Fletcher. “There is more to the study of frocks and hairstyles than you would think.”

Indeed, she believes Cleopatra may have committed suicide with a hollowed out hairpin, rather than by snake bite, while under Roman house arrest. “They had violent and volatile lives and had to have an escape route. It’s the perfect way to administer venom,” she says. “A hairpin that changed history.”

She has examined ancient letters and notes found in the village of Deir el-Medina, home to generations of stone workers and artisans who built the tombs of the pharaohs in the Valley of Kings. An unusually high number of villagers here were literate, due to the fact they had to understand technical instructions, and their notes were perfectly preserved in the dry desert heat. “These texts are hugely important. They are the equivalent of today’s texts or post-it notes and just reading them today gives you great insight,” says Prof Fletcher.

“A shopping list might seem boring but it tells us what they were eating and drinking. One note simply says ‘Come to a party’. Who doesn’t like a party? “

The Deir el-Medina collection includes everything from self-help manuals and medical texts to ghost stories. There is even reference to ancient sanitary towels. And one 3,400 note from a rich man to his bone idle tenant farmer particularly made Prof Fletcher laugh. Pick me many plants, lotus blossoms and other flowers to be made into bouquets. And don’t be lazy! For I know you are lazy and like eating in bed!” “It’s just so human,” she says.

Among her favourite characters are an architect called Kha and his wife Meryt. “This guy was dynamic – he lived into his 70s when people lived on average to 35 – and was responsible for three royal tombs in succession.” Kha’s tomb, which contained architect’s equipment as well as food and clothes, was found intact and chemical analysis, X-rays and CT scans revealed he had 14 gall stones. “He had lost most of his teeth and a lot of his food was minced up. This poor, toothless guy, and they were feeding him pulverised greens in gravy.”

In her book, Prof Fletcher also reveals that mummification began almost 2,000 years earlier than previously believed. The vast majority were buried in holes in the sand. “Their mummies are often better preserved than royal mummies and their bodies tell us so much.”

She describes the preparations for the next world as like a Christmas club. “There is so much care taken in even the most modest grave. It was something you saved up for, with everything there to equip them for the next world.”

She is just as passionate when talking about modern Egypt and spends weeks at a time in the country, having been ‘adopted’ by an Egyptian family living on Luxor’s west bank, close to the Valley of Kings, after her taxi driver asked her back to meet his mother and sisters in 1991.

“There were 14 of them in one house. Every time I go, I visit and have a cup of tea or stay over. They are just the best people and it is such a privilege to sit with them.”

Prof Fletcher finds the ancient past reflected in the everyday things around her there, from the type of bread they eat to the houses they live in. “And the modern stuff is just as interesting. Egypt just gets under your skin.”

She has never felt unsafe there, she says, and has even learnt some Arabic. “My accent’s rubbish though,” she laughs.

*The Story of Egypt by Joann Fletcher (Hodder & Stoughton, £25)

* A new four-part series, Immortal Egypt with Joann Fletcher, starts on BBC2 on Monday, January 4, at 9pm

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here