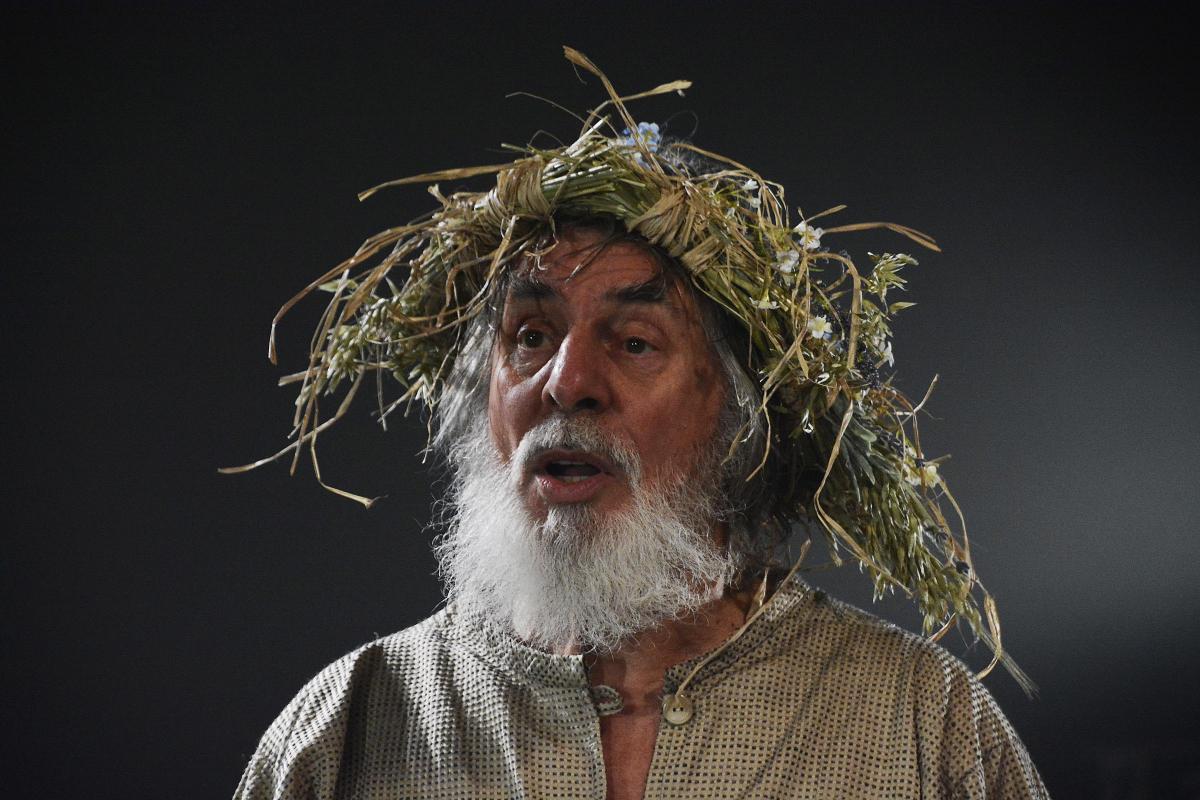

Nick Ahad talks to director Jonathan Miller ahead of bringing King Lear to North Yorkshire

Jonathan Miller's career has covered many different fields: author, lecturer, television producer and presenter, theatre, opera and film director. He co-wrote and appeared in Beyond the Fringe with Alan Bennett, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore which opened at the Edinburgh Festival in 1960 and later transferred to London and New York. His theatre productions include The Merchant Of Venice with Laurence Oliver, The Taming Of The Shrew (RSC) and as artistic director of the Old Vic Andromache with Janet Suzman and The Tempest with Max Von Sydow. His opera productions include The Marriage Of Figaro, The Turn Of The Screw, Rosenkavalier, Cosi Fan Tutte and Rigoletto. Television credits include his 1966 film Alice In Wonderland and 11 plays for the BBC's Shakespeare series. In June 2002, he was knighted in the Queen's Jubilee birthday honours list.

Many consider you a polymath, but you don’t like the word?

I hate the word polymath because it’s meaningless. My father was an accomplished painter and sculptor and writer but he was also the founder of child psychology. He would have been appalled if anyone said he was a polymath or a renaissance man or any of those things. He was just a man, like many of that period, who took pleasure in pursuing his varied interests.

Do you ever have a plan?

No. It just comes up one after another. Most of the requests I have had to do plays or operas have been unsolicited invitations that I have not asked to do. I mean there are several things in the early days when I went to the BBC and asked if I could make things like Alice in Wonderland or Whistle and I’ll Come to you but otherwise I undertook to do what I was asked to do in the belief that I would be able to do it.

Do you ever stop and look back on your extraordinary career? No. I get told it’s extraordinary and people start using these ridiculous terms like polymath and all that sort of thing. I sometimes look back at the age of 80 and think “was it all worthwhile” and “ought I to have done that, ought I to have left medicine”, for example and then an invitation comes up and I am engaged in nothing other than doing whatever is I was invited to do.

Even though it is an extraordinary career?

So I am told. The first play I ever did was at the Royal Court and I was asked to do it and I remember saying I don’t what it’s like I’ve never directed a play. I was assured that I would pick it up as I went along. I don’t know why they thought that. When I did direct I learnt to my pleasure that one of the skills I had picked up as a doctor, as a diagnostician, watching what people do was transferable to encouraging people to do things that were realistic in theatre.

A very particular skill?

It just is observationalism. I was encouraged when I was learning to be a doctor to look at what people did and getting hints as to what might be wrong with them. I never take taxis I always go on public transport and I watch what people are doing - reading newspapers, chatting to each other, looking at the list of places where they need to get off, things like that, those trivial details are all that we do as normal creatures. But people don’t notice that and what I have spent my time doing as a director is restoring the commonplace and the ordinary to performances.

King Lear seems a play to which you return.

I enjoy it and I think it is one of the best plays that Shakespeare ever wrote. I have been asked to do it several times. I think all in all five different performances and two television performances. It’s not that I am tremendously interested in doing it. I do enjoy doing it and am pleased to come back and reconsider it but I don’t make dramatic changes when I do.

Why is it such a special play?

What’s extraordinary is the strange realism of the behaviour of a person who in fact is an incompetent monarch. In the case of Lear we have someone who, as his daughter says when he goes out of the room, “he has ever but slenderly known himself” and that he was actually a foolish old man and probably a foolish young one. It may well be the fact that many people who inherit monarchy are not in fact qualified to exercise monarchy.

How much have you had to do with casting?

Not a lot, since I have worked with Barrie (Rutter) in the past, I know he has a company who have always been exponents of naturalistic skill and therefore I left it to him when I did Rutherford and Son and I have confidence in him doing it now for Lear. I gave him one or two recommendations about how old certain people should be - the fool should not, for example be young. Even though he is endlessly referred to as boy, he is not a boy, he’s an old man the same age as Lear.

Why do you enjoy working with Broadsides?

They are very naturalistic and unpretentious. I am sure I will find, when I direct this Lear, a group of people with whom I work quite naturally and don’t have to boss around. I think too many directors are too bossy and tell people that they must raise their hands at this exact moment right there. That is not what I director should do.

What’s your take on the state of British theatre?

I never go to theatre I don’t have an opinion I don’t see enough of it. I do what I do and the rest of the time I do the things that I am interested in, which is writing my books or making TV programmes until someone asks me to do a play or an opera.

Is there anything left to achieve?

You get to be 80 and you don’t get asked. Barrie rather flatteringly asked me to do this as he did with Rutherford and as that was rather successful I imagine this will be pretty good.

You and Barrie must be a formidable team?

We get on very well, there are obviously moments when he might disagree with me about something and then we come to some sort of settlement. I don’t think of myself as an important personality and I’m sure Barrie doesn’t. He just has been doing Northern Broadsides for a long time and has become a very distinguished member of the theatrical profession.

Why should audiences see this production?

Because it’s the next version of Lear, that’s all. They have reasons to expect it will be interestingly original and draw their attention to aspects of the play which they had not previously noticed, that’s all. I think the same is true of Barrie. We disclose previously unacknowledged aspects of the work and they will say oh yes, I knew that, why hadn’t I noticed it before?

What’s your take on Broadsides?

I very much enjoy the company, one of the most important companies in the United Kingdom. I wish that more recognition was extended to it. There is a curious metropolitan complacency about everything that occurs in the National Theatre and the big theatres of the West End and once it goes North of Watford it’s sort of negligible, which is one of the things I deplore about the English artistic world.

- The Round at Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough, re-opens for Northern Broadsides production of Shakespeare’s King Lear (April 21-25). Box Office 01723-370541 or sjt.org.uk

- York Theatre Royal, (May 12-16), yorktheatreroyal.co.uk or 01904-623568

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here