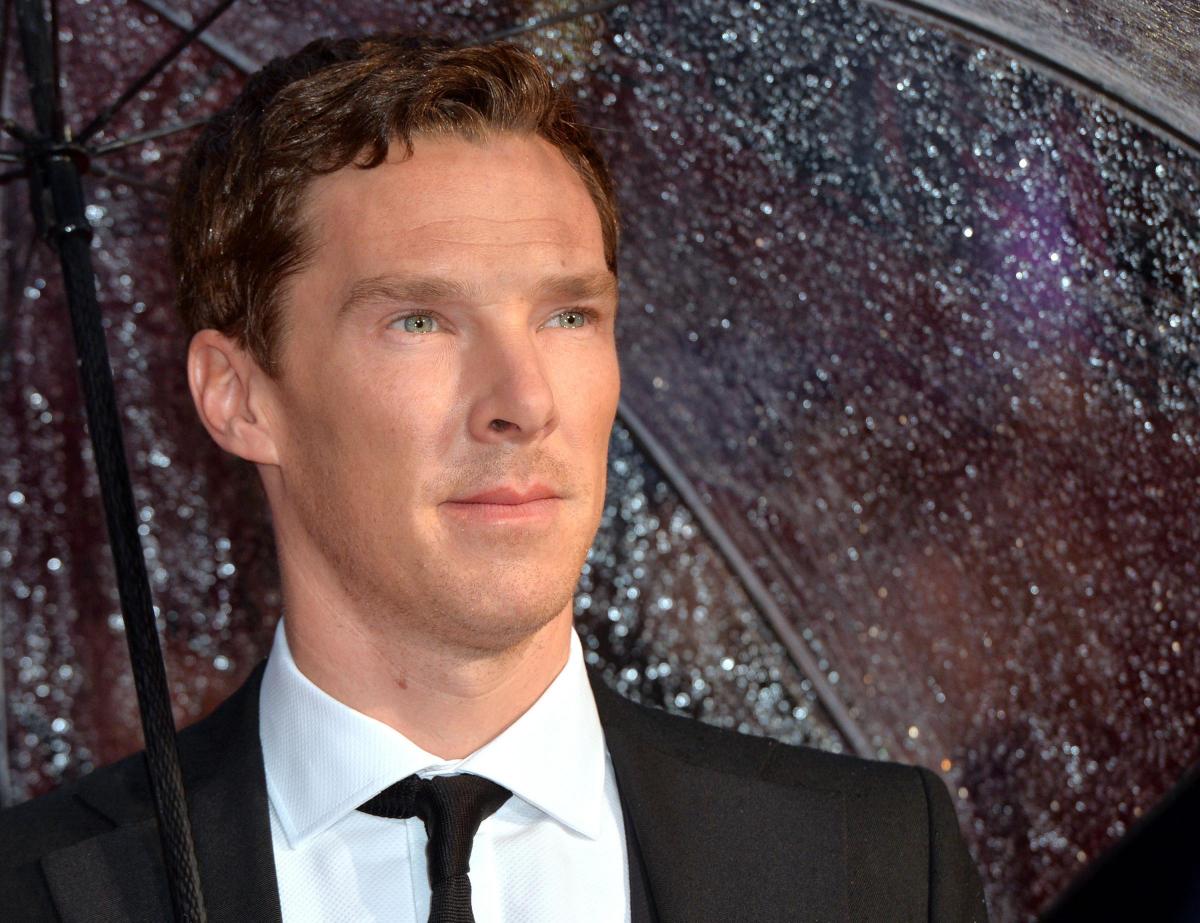

Newly engaged Benedict Cumberbatch plays brilliant codebreaker Alan Turing in biopic The Imitation Game. He tells Steve Pratt why this Bletchley Park genius is nothing like Sherlock

BENEDICT Cumberbatch wants to act stupid. The actor who’s found acclaim and fame on both sides of the Atlantic with his portrayal of supersmart supersleuth Sherlock Holmes in the BBC-TV series would love to escape playing brainboxes.

A decade again he won his first Bafta TV nomination as scientist Stephen Hawking in a TV film about his early days at Cambridge University. Then there was Sherlock, no slouch in the intelligence department either. Now in the new film The Imitation Game he’s tackling another real life character – mathematician Alan Turing, whose codebreaking skills helped defeat the Germans in the Second World War and whose work heralded the age of computers.

Cumberbatch plays Turing, a homosexual at a time when it was a criminal offence. After being prosecuted in 1952, he chose chemical castration over imprisonment. He committed suicide two years later. Only recently has he been given a royal pardon and his ground-breaking work officially recognised.

The actor can’t escape the shadow of Sherlock whatever role he plays now. No-one is going to let him forget it. But having played one “social abrasive heroic genius” on the small screen he didn’t feel any pressure to give Turing nuances and personality traits to make him different to the Baker Street detective. “Well, I’m limited by who I am and what I look like, but at the same time they’re utterly different people,” insists Cumberbatch at the press conference for The Imitation Game, ahead of the film opening this year’s BFI London Film Festival.

“Alan doesn’t swish around in a long coat with curly hair demonstrating how brilliant he is. He’s a very quiet, stoic, determined and different type of hero. He’s smart, but an outsider because of the conditions of his personal life. As for the similarity that he’s socially awkward – what you see in the film is an evolution in him which is humanising. That happens in some aspects with Sherlock, but I didn’t read the script and think, ‘This is Sherlock in tweed’.

“I liked how uncompromising Turing was, but that’s always a strong trait in strong characters. I have played stupid people as well. I want to point that out. So if anybody’s got any more stupid roles for me, great, bring 'em on.”

He finds comparisons between characters frustrating, but adds, “They’re understandable”.

The film follows a group of mathematicians working to crack the German Enigma code with Turing developing a machine which decoded intercepted Nazi messages. His work helped shorten the war and saved thousands of lives. Cumberbatch hopes the film gets Turing’s story known to a broader audience. “He was wronged by history,” he says.

“There’s a disparity between his importance and prevalence in our modern culture, as well as what he achieved in the 20th Century, and the comparative lack of knowledge of the full span of his story and life. The idea of getting a broader picture of him out there did carry the weight of importance. It’s his legacy.

“It’s been an extraordinary decade for him because of his centenary, official pardon from the Queen and now this film. It’s all part of that momentum to bring him the recognition he deserves as a brilliant scientist, father of the modern computer age and a war hero. We remember a man who lived an uncompromising life at a time of disgusting discrimination, contextualised by the fear of the red threat of communism.”

He guesses that the official secrets act has kept Turing’s life and work under wraps for so long. “There’s a dark stain of shame of the government’s hand in persecuting thousands of men for their sexuality for fear of communist sympathies,” he says.

“I guess the idea that somebody’s work, which in the sphere of pure maths is devoid of geopolitical interest or any kind of culture of celebrity, means the true amalgamated importance of the man is his life as well as his work. And that’s only just slowly become acknowledged. Why couldn’t his posthumous pardon have come earlier? I don’t know.

“It would be very interesting to know why, because you immediately feel a sense of injustice playing a man treated as appallingly as he was, and whose achievements have not been conglomerated into the fuller picture of who he was. As a society, if we live through a very secretive or shaming era we’re very good at overlooking things. It’s dangerous to do because the smell from underneath the floorboards is eventually impossible to ignore and hopefully this film will do something to expose the truth of what happened to the man.”

Researching the role wasn’t easy because no visual or audio recordings of Turing exist. Graham Moore’s script and director Morten Tyldum’s research guided him towards building up a picture of the man. He was also lucky enough to meet people who either had met him, or were related to him. “They gave me accounts which were helpful to personalise this extraordinary man, who we only know in broad headline terms,” he adds.

In the film, Turing’s sexuality is expressed, but not shown explicitly. Neither, Cumberbatch points out, is heterosexuality. “He had to suppress his sexuality, make it private, make it something secret. When he talks about his sexuality in the film it shows his complete honesty, guilelessness and innocence. He was aware of the risks, but at the same time wasn’t willing to cave in to the intolerance and potential permutations of confessing such a thing.

“Some people own him as a martyr or as standard-bearer for a cause. I think he was just very true to himself, which is a form of martyrdom, but he didn’t make a political statement out of it.”

There’s already buzz of an Oscar nomination for Cumberbatch. If such talk gets people to see the film that’s all he cares about. It’s very flattering, but there are a lot of other extraordinary films and performances people haven’t seen yet,” he says.

“But if it creates an interest for people to see what all the fuss is about then that’s fantastic, because our jobs as storytellers are made easier if there’s an audience. And more importantly for me, having had some experience with this man, I really want his story to be known and our film to be a launching point for a proper celebration of Alan Turing.”

The Imitation Games is showing in cinemas

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here