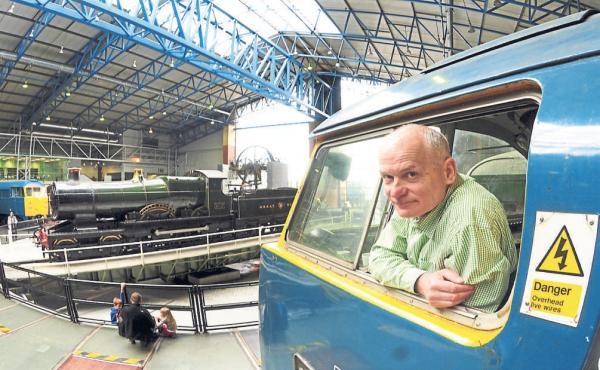

YORKSHIRE-BASED poet and broadcaster Ian McMillan was well-qualified to climb aboard the National Railway Museum’s Trainspotting season. “They knew I was a chap who didn’t drive and liked trains,” he says at the York museum after a photo session with some of the grandest engines in the collection.

“When they asked me, I was excited about it because I’m fascinated by trainspotting, not only the anthropology of it, but also the heroism of it in a way. I’m going down to London a lot and look across the platform and see all these trainspotters. I’ve often wanted to approach them or talk to them, but it seemed like they might think I wanted to take the mickey.

“Years ago in Doncaster Arts I had this idea of doing a musical about trainspotters, but you always come up against the thing they’re thinking you’re going to take the mick.”

The NRM took a different approach by asking trainspotters to send in their tales of the track. McMillan is sifting through these stories to display around the museum during the Trainspotting season beginning later this month. He’s also written a poem “that encapsulates the adventure of it, sometimes the disappointment of it, the way that it happens in all weathers, that it’s a thing that bonds families together,” he says.

“In a way trainspotting is a bit like Game Of Thrones because it’s a quest, but with no nudity, except accidentally. I like the quest nature of trainspotting. It’s like an epic poem, it really is – you’re off to find something, you look for it, you don’t find it today, you find it tomorrow.”

What he’s always wanted to ask trainspotters, but never plucked up the courage to do so, is ask what they do when they’ve ticked off all the trains and there are no more to spot. “Then what do you do? Pretend you haven’t? Go and find some more? Invent a couple more? Turn to birdwatching?”

The Trainspotting season aims to explore the past and present of the pastime of collecting and documenting trains as a hobby. So far the NRM’s research has unearthed that the first trainspotter was a 14-year-old Victorian girl, mentioned in a magazine article. But her motives for trainspotting remain unknown.

McMillan was briefly a trainspotter as a young man but “because I’m more of a fantasist than a realist I wasn’t very good at it”, he admits. “I remember me and my mates being at Oulton main pit and having these binoculars – my dad’s when he was a sailor – and us pretending we could see things when we couldn’t. So a couple of pit wagons would go by past and we’d say, ‘I don’t want you to get excited but I think the Mallard’s going through now’ or ‘I think it’s Stephenson’s Rocket’. Then you realise that’s being daft. “I also have a vivid memory of standing by on a Sunday when they used to divert trains through on the main line. You’d see things like the Devonian and the Thames-Clyde Express. Me and my mates were standing there with our shorts on like extras out of Kes looking at this train as it went past. “It slowed down and we were opposite the restaurant car. There were all these besuited toffs sitting being served by chefs. We’d go ‘hello, mister’ and the besuited toff went like this, sticking two fingers up at us. That told us quite a bit about the class system. We ran home and told our mams.”

That was the end of him as a trainspotter, but sometimes these days waiting for a train at ten to six in the morning at York Station he sees spotters and wonders about getting out his notebook and writing down a few numbers.

“I don’t because I can see it could become addictive, that’s why I’m a bit nervous about taking it up again.”

He rejects the idea that trainspotting isn’t a very social activity. When there’s a lot of them they tend to talk in their own code “like saxophone enthusiasts or people who collect plugs” to each other. At Doncaster station he’s seen whole families. “They’ve come with foldup chairs and often seeing the train is almost secondary to meeting their mates. Again they talk about it in their own terms – ‘I haven’t seen you for a couple of days Frank’. ‘Yeah, I had to get down to Penzance to catch the Cornish Riviera’. They go off on these quests.”

He feels the Trainspotting season is a great idea and doesn’t understand why it hasn’t been done before. Amy Banks, interpretation developer at the NRM, hopes the season will show trainspotters or train enthusiasts in a fresh light.

“It’s an important part of railway history that has never really been talked about before,”

she says. “We want to give an insight into the pastime by hearing from trainspotters themselves. The stories they have sent us have been funny, light-hearted, humorous. They have this wonderful lyrical quality to them as well.

There’s lots of recurring themes about travelling all over the country, adventure, drama and a bit of mischief in that early period of being in places they shouldn’t be.”

The museum has also commissioned artist Andrew Cross – who describes himself as a “lapsed trainspotter” and now a trainwatcher – to create a new piece of work in the NRM’s gallery space.

His exhibition will feature archive material from his early days as a trainspotter together with new film collected internationally.

“It’s about the moment of being there, of experiencing it. He’s searching for different trainwatching scenarios in Britain, America, Switzerland and all around Europe. For him, the appearance of the train is the end of the series of adventures you went through to get there,” says Banks.

- Those with trainspotting tales, including poems, should contact Amy at amy.banks@ nrm.org.uk or post pictures and stories on the museum’s website nrm.org.uk/NRM/ GetInvolved/trainspotting.aspx. Images can be submitted via twitter using #trainspotting @railwaymuseum

- Trainspotting runs from Sept 26-March 1 at the NRM in York. For more information visit nrm.org.uk/trainspotting

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here