OMID Djalili gives great cuddles. I know this because, after an hour spent giggling and listening intently in a cosy corner of a private members’ club as he recounts tales from his early life, I pluck up courage to ask for a hug.

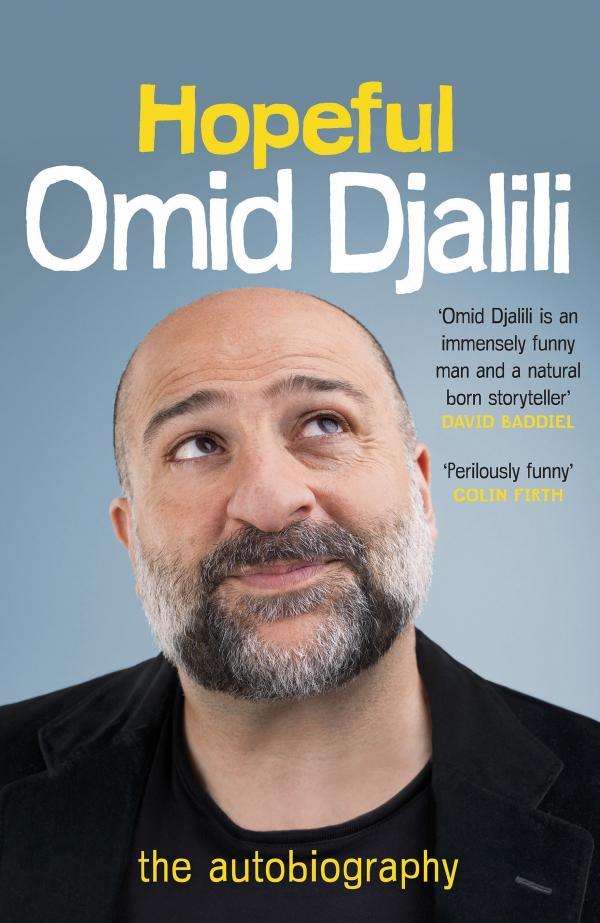

There’s a chapter in the comedian’s new autobiography Hopeful, where, as a wideeyed schoolboy, he meets Mel Smith backstage at his school play and asks, ‘Can I hug you?’ “It felt so comforting, to be held by a ‘daddy bear’ type like him,” he says, admitting that, even then, he knew he too had daddy bear potential.

It’s official, Omid Djalili has nailed the daddy bear thing. Not only is he cuddly and funny, he’s also extremely down-to-earth in person – there’s not even a publicist in sight.

And his book is packed full of wisdom.

It focuses mainly on his life growing up in a large flat in Kensington, the son of Iranian parents, who ran “a sort of guest house” for fellow Iranians, who were seeking medical care in the UK. Djalili spent much of his time sleeping on the sofa to make way for paying guests and, left to his own devices, developed a keen sense of imagination.

He retook his A-levels four times and eventually managed to blag his way into the University of Ulster in Coleraine. While there, he decided to go for broke and, during reading week, flew to the US to get himself a place at Princeton.

“I’d seen films like The Graduate, and this whole thing of Ivy League universities was very much in my head, so I thought I could blag my way in,” says the 48-year-old fatherof- three.

Impressively, after stealing a door pass, he managed to attend a lecture and have an interview with the vice chancellor.

“I was trying to get a scholarship, and said I was a remarkable footballer. He took one look at me and said I wasn’t really his 1986 cohort.”

You might call this the delusion of youth. I call it having extraordinary self-belief. “I’ve always felt that I wasn’t stupid, but I don’t know where this hopeful attitude came from,” he says.

Djalili unleashes his deep belly laugh while retelling a story about a young Michael McIntyre – someone else who believed in himself – asking him for advice, and adds: “A lot of people are deluded. I probably was deluded. But I was lucky enough that something went right along the way.”

Something has definitely gone right, but it seems Djalili has got where he is today – one of the country’s most beloved stand-ups, who’s had roles in films including The Mummy, Sex And The City 2 and Gladiator (more of which later) – against all odds.

He nearly drowned in a cesspit during a visit to relatives in Tehran as a child – an incident which he describes in hindsight in the book as hilarious, but which could have been a disaster – and he was shot at by drunk Protestants while at uni in Northern Ireland. Having earned a 2:1 in humanities, he auditioned unsuccessfully for 16 drama schools, and drove limousines for the likes of Arab royalty around London for a decade to make ends meet.

Sticking two fingers up at the drama school ‘establishment’, Djalili managed to land himself work as a jobbing actor – and fell in love. His tenacity came into its own when he spent years courting his now-wife, Annabel, even moving to Czechoslovakia at one point to “demonstrate detachment, dynamism and a pioneering spirit”.

“She said to me, ‘I had to marry you because you just wouldn’t say no. But I knew things would be difficult’. And actually, they were, because I was so focused on having a career and doing well. Let’s just say it was persistence. She’s often said [to our children], ‘Be persistent like your father’.”

He tails off at this point to offer me a cup of tea.

“I think it comes from being hurt actually,”

he admits. “From being rejected. Because I was in this crazy house with so many people and very much left alone.”

“But you were well loved...” I venture.

“Yes, what I tried not to push too much was the sense of neglect. The [house] guests were always more important and I just found my own way.

“You have to say thank you for all the people who weren’t there for you, because ultimately, it gave me that self-belief to keep pushing.”

Djalili’s parents always thought they’d return to Iran one day. But in 1979, the Islamic Revolution saw the country become a republic and people of his family’s Baha’i faith were rounded up and killed. He hasn’t returned since he was six and says it would be dangerous to go now.

“I’d probably get banged up. The Baha’is are very much seen as an apostate religion.

They probably wouldn’t do it to someone as high-profile as me, but I couldn’t take the risk.”

While Djalili never experienced any racism growing up in 1970s London, apart from the odd “dodgy old man” who called him “exotic”, when the Islamic Revolution hit headlines, he assumed a “survival alter ego”.

“The revolution was on television every day. It was a long period of my life and I just got sick of it,” he says.

“I was a very nervy adolescent – I had a moustache and started going to parties and saw girls from different schools who didn’t know me. So I became this kid Chico and pretended I was Italian. For about a year and a half, I was being someone else.”

In his book, Djalili reveals he “craved the limelight” from a young age, which was spurred on, in part, by his mother’s visit to a psychic, who predicted: “Your third child is going to do something spectacular. He will be known throughout the whole world.”

Then at university, he had “a moment on a beach when I was shouting at this god in the sky”.

“I said, ‘What do you want from me?’ And it seemed very clear from the answer that was in my mind – but it could have been a hallucination through staying up all night. It said there was a path to follow in showbiz. It wasn’t clear that it was acting, but I knew it was somewhere in the world of show business. Which I was damaged enough to fit in,” he says, laughing.

Although now best known for his stand-up, he only came to it aged 30.

“It was something I actually succumbed to in the end. It kind of chose me after years of people saying, every time I went up on stage there were gales of laughter – sometimes inadvertently.”

He’s about to go on a massive, eight-month-long, 98-date tour of the UK – called Iranalamadingdong – which will focus less on his background and more on getting older.

But he’s also making his film directorial debut with a drama about gang warfare among Asians in the Midlands, which is “epic and very British”.

“I’ve always wanted to make serious films.

Comedy’s important, it’s very good to laugh. But when I look back at all my favourite films, they’re all drama. I remember thinking I love Gladiator...

I can’t believe I’m in it.”

And while we’re on the subject, his experiences on set of the Oscar-winning film make brilliant reading.

The late Oliver Reed, who died during filming, played a practical joke on Djalili. When they had a scene together, rather than punch Djalili’s slave trader, Reed grabbed him by the balls and held on for three takes. Djalili recalls: “By take four, I became slowly and unnervingly aware of a massaging sensation.”

“If people play tricks on you, they like you,” he says now. “The majority of the crew were from The Mummy, amazingly, and I’d stupidly mentioned I was scared of Oliver Reed. Ridley Scott said, ‘We’ve changed the script, I hope you don’t mind. He’s gonna grab your balls.’ I went, ‘Fine!’ You want to impress a big-time director so you get on with anything. I didn’t know it was all a set-up.”

Even more bizarrely, the producers then decided that as Djalili seemed game for a laugh, he could be a useful “bridge” to help lead actor Russell Crowe come out of his shell and relieve tension on set. But it backfired when Crowe misinterpreted Djalili’s friendly advances.

“He thought the producers assumed he was gay and had sent me as a gay guy to befriend him. It was the way I said, ‘We’ll take off our shirts, play a bit of pool...’ I think he said: ‘Even if I was gay, why would I want to be with a fat c*** like you?’”

He breaks off into peels of belly laughs again, assuring me it was all in good spirits and there are no hard feelings between him and Crowe. It must be the daddy bear effect, I think, as I sneak that cuddle and see him off to record the audio version of his book.

- Hopeful by Omid Djalili is published in hardback by Headline, priced £20. Available August 28 n Omid Djalili’s Iranalamadingdong starts on September 18 at the Epsom Playhouse and runs until March 28, 2015, taking in Harrogate on October 6, Whitley Bay on January 21 and York on February 9. For more details, visit omidnoagenda.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here