THIS week, iron and steel maker SSI had planned to unveil a multi-million pound investment that would help its Redcar works to compete with the best in the world.

Start-up on a £38m pulverised coal injection facility (PCI) has now been pushed back to May.

Installing PCI could make the Thailand-owned company an extra £62m a year in savings and additional revenue. Put another way, every week the project is delayed could cost it in the region of £1m.

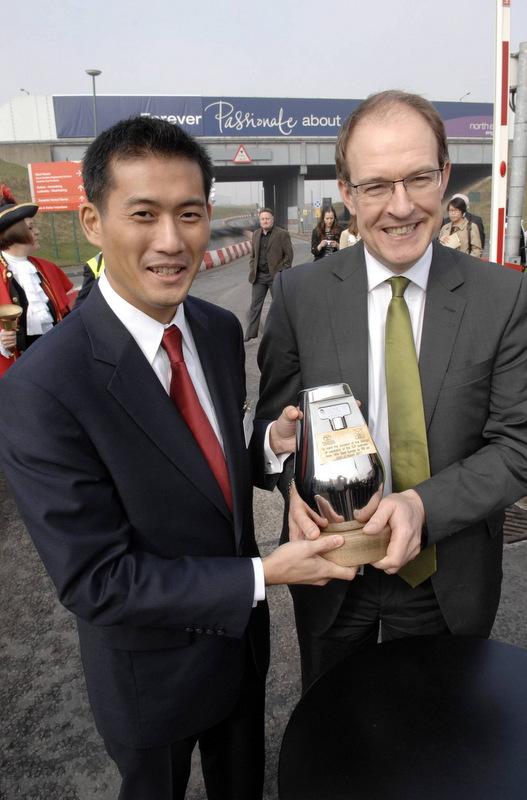

Phil Dryden, the SSI UK boss, admits that without PCI the Teesside operation would struggle to compete. So I was surprised to hear him speak with such optimism when we met last week.

Was this the typically cheery facade that bosses put on for the media, or a sign that the steel man truly believes the company, which has suffered serious cashflow problems, is through the worst?

On the firm’s darkest days last year, John Baker, Mr Dryden’s trusted head of communications, would look at his boss every morning to gauge his mood. If Mr Dryden gave him the “thumbs-up” sign then John knew the business was okay.

“And on bad days?”, I ask Mr Dryden, who pulls the kind of face you would expect to see on a tightrope walker who has started to wobble, and wonder if their high wire act is about to come to an abrupt end.

“That’s the look I would give him,” recalls Mr Dryden, laughing.

“There were maybe two or three days when I thought we had lost.

“I don’t expect any days like that this year. It’s not going to be easy. There are months of hard work ahead of all of us, but I can see the light.”

The faint glow that Mr Dryden has fixed his gaze upon is coming from 8,000 miles away.

SSI UK’s parent company ended last year strongly. The Thai firm’s hot-rolled steel mill, where slabs made on Teesside are turned into shiny sheets of metal used to make cars and white goods, hit record production in the last quarter. The Thailand side of the business has also edged back into profit.

The prospects for 2013 look even better with rolled steel prices tipped to rise further and the company’s order book already full. SSI is the leading hot rolled steel firm in Thailand but it wants to increase market share; strike bigger deals and become a major player in South-East Asia. Having its own steel plant will be key.

Mr Dryden adds: “I go there once a month and see a country that is booming, with six per cent GDP growth. I see steel prices going up and SSI Thailand making money. This is all good. The only risks for the group lie here in Teesside.”

Mr Dryden has called 2013 “Our payback year” when the UK operation must repay the faith shown by its Thai owners who bought and revamped the Redcar plant at huge expense and funded all of the working capital.

Its balance sheet has improved but Mr Dryden admits the losses incurred by the UK operation last year run into hundreds of millions of dollars.

The drain on the parent company was so severe that Win Viriyaprapaikit, SSI’s chief executive and president, made the painful decision to sell shares in the company he took over from his father.

That will inject about £100m into the business, much of it in staged payments, with more to follow.

Mr Dryden declines to reveal how much of the cash he has been given to help balance his books, but it’s fair to say that he would have liked more to appease those suppliers who have been waving unpaid bills under his nose.

Mr Viriyaprapaikit even offered creditors an equity share against arrears owed.

Mr Dryden continues: “For a family business like SSI it was the last thing they wanted to do.

No one would relish the prospect of diluting their stake in a business they have built up themselves. But, for me it shows the level of commitment they have to Teesside.

“No one really knew SSI two years ago. People asked – have they got the passion, hunger and commitment to keep this thing afloat if times get hard? I don’t think anyone can ask that now.

“They had never been a lossmaking business until they inherited us. Right now we are a burden to them.”

PCI will turn Teesside into a profitable asset. Mr Dryden reckons it will help to nudge SSI UK into the black by the end of this year.

“Telling Win (Viriyaprapaikit) that PCI was delayed wasn’t the best piece of news I’ve carried to Thailand,” he reveals. “It is a major disappointment because this project should be easier than the restart of the blast furnace.”

Why the delay?

“Building it in the middle of winter isn’t ideal,” explains Mr Dryden. “And we had a lot of industrial relations problems with walk-outs and strikes – among construction workers, not SSI staff.

“We are not far off the beach so you can dig for ages before you hit something solid. We had to go deeper on foundations and put more concrete in than we anticipated.”

Most bizarrely, at a time when the construction trade is desperately short of work, he also struggled to get enough skilled fabricators on site.

“The PCI build has always been under-resourced. I don’t know if it’s because people have been making North Sea wind farms or whatever but we struggled to get enough of the right people on site. In a way it’s a positive thing for the North- East that there was a lot of work around for fabrication, steel erection and metalworking, but it held us back.

“We found with the blast furnace, which hasn’t suffered a blip since restart last April, that there is no point cutting corners if you want these things to be reliable and deliver long-term benefits to the business.”

Instead of lumps of expensive coke being fed into the top of the iron making process, the PCI system injects powdered coal into the base of the blast furnace, making the whole process cheaper and more efficient.

BARRING any more problems, the top-of-therange plant supplied by German firm Siemens VAI will soon sit beside the blast furnace, giving SSI the potential to boost output from 8,500 tonnes of iron a day to 10,000 tonnes.

“I think we have turned the corner,” adds Mr Dryden. “Our connectivity with Asia means we are in a position to recover much quicker than if we were wholly reliant on the European steel sector, which is struggling to fill order books.

“We’ve been victims of the market rather than of our own operational delinquencies. It’s been hard, probably harder than I expected with the falling price of steel slab hitting our margins right from the off. Last April, we were a newborn baby that came into the world when a storm was raging, but we survived.

“PCI being commissioned is the pivotal moment that will help us to right ourselves. This is the piece of the jigsaw that has been missing for Teesside.”

Knowing what you know now would you still take this job?, I asked.

“Yes it’s been great,” says Mr Dryden. “I signed up to see this through and I won’t rest until we do. It’s a massive step up for us. Now we are getting to the finishing straight we all need to step up as an organisation.

“Culturally, parts of this business still have an element of British Steel in them where people think that this is a job for life and we are the best in the world. That attitude is something I have to work on.

Look over your shoulder – the rest of the world has caught us up, or overtaken us. If we don’t improve we are going backwards.

People here need to recognise that.” he says, with such obvious enthusiasm there is no need to look for a thumbsup.

Fingers crossed.

Why is PCI so important?

- PCI uses coal, a cheaper product than the coke currently used by the blast furnace.

- Powdered coal will be injected into the furnace instead of lumps of coke – boosting efficiency.

- Feeding coal into the bottom of the furnace cuts the time it takes to make iron.

- Iron production will rise from 8,500 tonnes per day 10,000 tonnes per day.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article