YELLOWING and dog-eared at its corners, a single page torn from a newspaper lies shrouded in an archive file.

Unfolded from its brown folder, the broadsheet-sized artefact discloses 30 years of rich North-East manufacturing history.

‘In the next 11 years’, a 1985 advertisement screams, ‘Nissans should be exported by a small island with a highly-skilled workforce’.

With Great Britain printed proudly in capital letters down the spine of the country, itself surrounded by a grey line marking its waters, the black and white full-page graphic goes on to claim ‘in the 1990s, over 100,000 Nissans a year should be made in Britain’.

The only reference to Europe comes from thick black arrows spreading from the North-East into the North Sea, and a pay-off line declaring Nissan could become the continent’s top imported marque.

In this post-Brexit era, the irony of the UK proclaiming its prowess as a separate manufacturing landmass from Europe is not lost.

However, what it also interesting to note is Nissan’s production targets.

When the newspaper article appeared, in September 1985, workers were still turning the former Sunderland Airport into the Japanese company’s plant.

Its first model, the Bluebird, branded as a car for Europe, was still a blueprint drawing.

So its 100,000 production goal seemed a somewhat colossal target, particularly for an area where generations of workers grew up with skills more attuned to shipbuilding and mining than car manufacturing.

But, 30 years later, the plant has made nearly nine million vehicles.

Yet Nissan as a company is cautious and discreet in its nature, and takes a steady approach to its achievements.

It may well have its roots in Japan, but the business has quickly immersed itself in the North-East tradition of carrying out work with minimal fuss and fanfare.

Rather fitting then its first Bluebird, which rolled off the production line on July 8, 1986, did so without the glare and flashing cameras of the media.

The Northern Echo ran a story the day after the event under the headline: ‘Nissan plant keeps first car secret’.

Quotes from a spokesman said the business was keen to wait for work to rise close to capacity before letting the hordes of reporters through its doors.

Today, things haven’t really changed.

When bosses secure new models, such as the all-electric Leaf hatchback or the luxury Infiniti Q30, the news is feverishly devoured by the media.

However, once the celebration has ended, the company quickly returns to its status quo.

Its Sunderland factory is a Downing Street delight.

Prime Ministers, including Tony Blair and David Cameron, and their Cabinet members have regularly beaten a track to the site, using their trips to acclaim its employment and exports achievements while extolling the virtues of their associated policies.

Prince Charles has also toured its vast production lines.

In 1986, alongside Princess Diana, he was given the keys to the first Bluebird made at Sunderland and was back early last year to see work on the Leaf.

But, outside those blue ribbon events, manufacturing carries on behind closed doors.

It’s an attitude dating back to the 1985 advertising campaign.

‘They don’t half work’ said the text, referring to Nissan’s cars, yet it could so easily be used today to denote the commitment of its 6,700-strong Wearside workforce.

The team were previously responsible for giving the Sunderland plant record-breaking status, after it became the first UK manufacturer to make 500,000 cars in a year.

The feat wasn’t a one-off and similar triumphs came in subsequent years.

HOWEVER, it could have been all so different.

Black and white pictures of Norman Tebbitt, the Trade and Industry Secretary, smiling alongside Nissan president Takashi Ishihara as they signed contracts to mark the vehicle maker’s factory deal, hid the real story.

Secret government records show then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who helped bring Nissan to the region, had to step in when a dispute between Mr Tebbitt and Chancellor Nigel Lawson threatened the inward investment coming to fruition.

Nissan’s place in the UK came about because it wanted to sell more cars in Europe.

To duck import quotas it needed a European base and the British Government was desperate for the Japanese to come here.

But not everyone was welcoming.

Washington Labour MP Roland Boyes was vocal in his criticism of Baroness Thatcher being chosen to officially open the plant in September 1986.

Nigel Pritchard, operations director at Austin-Rover, said every job Nissan created in the North-East would destroy two in the West Midlands.

He also said Rover “wasn’t particularly impressed” by the low level of technology on Wearside.

But, once again, Nissan did its talking when it preferred and where it mattered: on the factory floor.

Sunderland soon overtook Rover’s massive Longbridge plant for productivity.

That focus began with the Bluebird, which was designed to lure drivers away from the Ford Sierra, Austin Montego and Vauxhall Cavalier.

Its first trial assembly car was made on April 22, 1986, three months before its first Bluebird available for commercial sale was produced.

Heralded as a beacon for the North-East’s future economic success, more than 20,000 Bluebirds were built in the first year and by February 1989, staff were lining up to mark the 100,000th model, two years ahead of schedule.

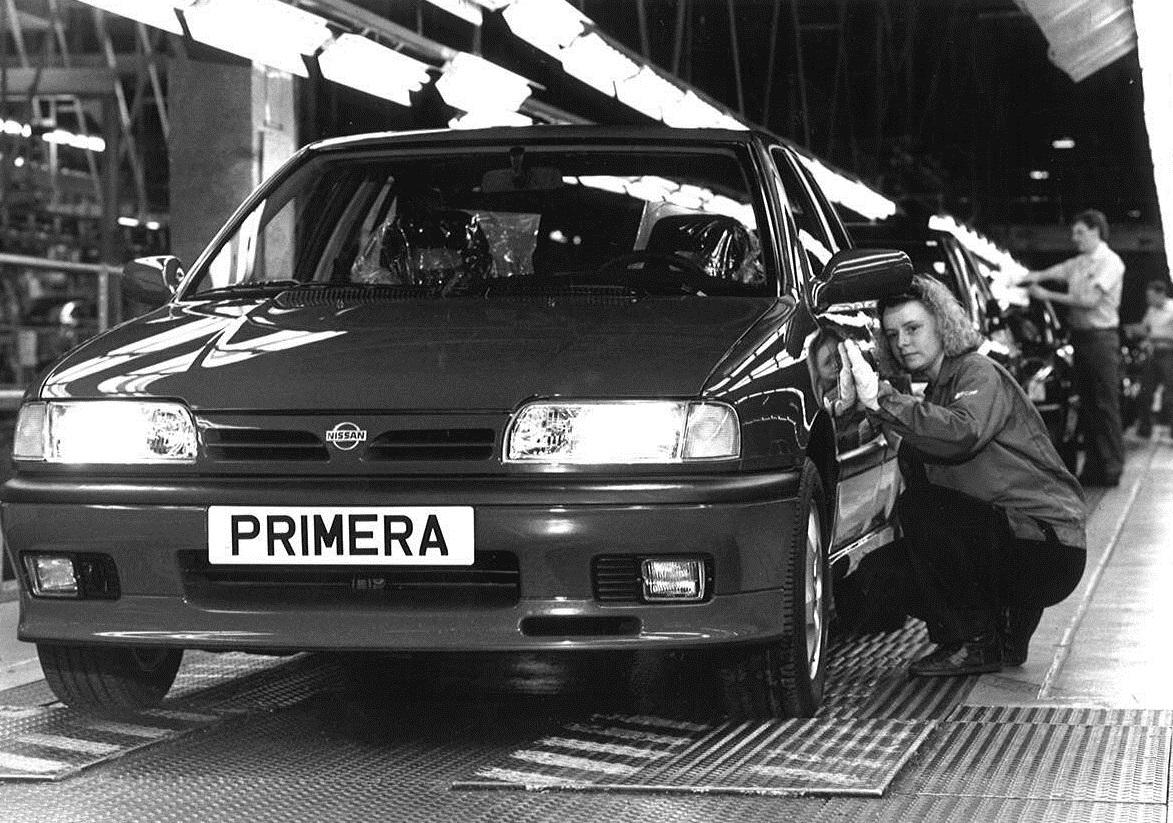

A year later, Bluebird production ended and work began on the Primera and in August 1992, manufacturing on the Micra hatchback got under way.

By 1998, Sunderland was the UK’s largest car plant, with the Micra helping push production beyond two million vehicles.

Bosses strengthened their market position in 2000 when they chose Wearside as the base for the Almera and took it further again in 2006 when they brought the Note and Qashqai to Sunderland.

SO extreme is the clamour for the Qashqai that Nissan is now spending £22m to increase production across its two lines to meet demand.

The vehicle, which was revised three years ago to give it a sleeker look and technological innovations, such as driver aids and parking assistance, is the factory’s best-selling model and rolls out of its doors alongside the Juke, Note and all-electric Leaf.

The rechargeable Leaf came to the region after chiefs sanctioned a £420m investment that created more than 500 jobs and gave the plant responsibility for building the car for European markets.

A sister factory makes batteries for the model, which was the world’s first mass market electric vehicle and gained the respect of Mr Cameron during a visit in 2013.

The Northern Echo exclusively revealed earlier this year that Sunderland will stop making the Note as it targets growth from extra Qashqais and a new Micra, now produced in France.

But Nissan isn’t resting on its laurels.

Borrowing ‘they don’t half work’ again, its Wearside base is now the home of the Q30.

The sporty hatchback is the first new car brand to be made in the UK on such a scale in 23 years and Infiniti’s first vehicle to be manufactured in Europe. The move represents a £250m investment in Sunderland and bosses say the Q30 will be crucial to breaking into the Continent’s premium car sector, where rivals such as Audi, BMW and Mercedes hold sway.

The car, which carries the marque of Nissan’s deluxe sister brand, will soon be joined by QX30, with both primed to become the first premium models to be made at Sunderland and exported to the US and China. They are yet another sign of the Japanese company’s commitment to the region.

Today, the plant has made 8.7 million vehicles.

The figure is a long way from the 100,000 advertised in 1985.

But then again, it shouldn’t be a surprise.

Nissan; they don’t half work.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here